Novel antibody breaks bacterial biofilms and prevents sepsis in mice

Posted: 2 March 2020 | Victoria Rees (Drug Target Review) | No comments yet

A new monoclonal antibody has been discovered which disassociates bacterial biofilms and stops bacteria from entering into circulation has been tested in mice.

Researchers have shown that a new therapeutic antibody can break apart communities of harmful bacteria, potentially opening the way for bacteria-killing antibiotics to more effectively clear out infections. The team, from the Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University (LKSOM), US, show that their novel monoclonal antibody (mAb) can open and break apart infectious bacterial biofilms.

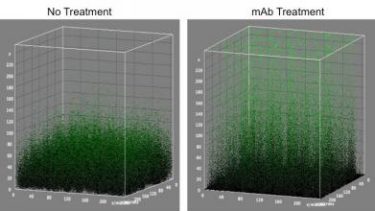

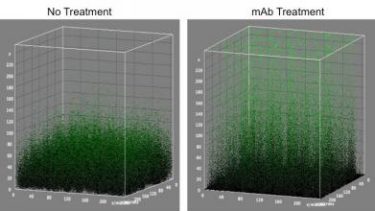

The monoclonal antibody treatment detailed in this research loosens up the compact biofilms allowing for combination treatment. This image shows this phenomena (credit: Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University).

“With this new antibody, we open the door for better treatment strategies for patients who suffer from chronic infections associated with implanted medical devices or who suffer from recurrent infections, such as repeated infections of the urinary tract,” explained Dr Cagla Tukel, associate professor in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology at LKSOM and senior author on the new study.

The new mAb, named 3H3, was isolated from a healthy human subject by Dr Scott Dessain, a professor at the Lankenau Institute for Medical Research and co-author on the new study. Dessain and Tukel were intrigued by 3H3’s ability to attach to β-amyloid, a sticky protein that functions abnormally in Alzheimer’s disease. A form of amyloid called curli is secreted by bacterial cells and is a major component of biofilms. Bacterial amyloid curli acts like glue, enabling bacterial cells to adhere to one another and form a continuous film over a surface.

In experiments with infectious Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, which forms biofilms in the human intestinal tract and on medical devices, Tukel’s team found that amyloid binding by 3H3 disrupted biofilm formation, causing the separation of bacterial cells within the film. The researchers then tested the antibody in mice infected with catheter-associated S. Typhimurium biofilm. In these animals, 3H3 injections also led to biofilm dissociation and when followed by antibiotic therapy, allowed for the swift eradication of individual bacterial cells from the animals.

While 3H3 broke the biofilm, it also prevented the dissociating bacteria from entering into the animals’ circulation, where they could cause sepsis. 3H3 was found to bind to individual bacterial cells, facilitating their uptake by immune cells. Therefore, this novel approach has the potential to reduce the risk of sepsis.

“We are very excited about these findings,” Tukel said. “There is great need for an immunotherapy that can be used alongside lower dose antibiotics or other antimicrobials to safely and effectively eradicate biofilms in infectious settings.”

The researchers plan next to test 3H3 on a wide variety of biofilms. As many important pathogenic bacteria produce curli or curli-like amyloids in their biofilms, including Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, this novel immunotherapy has the potential to be applied to a wide variety of infections.

“We also are developing a clinical approach,” Tukel noted. “Our pre-clinical findings in animals are promising and we’ve identified a clear path to clinical development.”

The study was published in the journal Nature Communications.

Related topics

Antibiotics, Antibodies, Antibody Discovery, Antimicrobials, Biofilms, Drug Targets, Monoclonal Antibody

Related conditions

bacterial infections, Sepsis

Related organisations

Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University (LKSOM)

Related people

Dr Cagla Tukel, Dr Scott Dessain