Scientists discover how membrane necks get constricted and cut

Posted: 10 July 2017 | Niamh Marriott (Drug Target Review) | No comments yet

Scientists at the Leibniz-Forschungsinstitut für Molekulare Pharmakologie (FMP) have succeeded in revealing a key mechanism of membrane deformation.

Scientists at Freie Universität Berlin and the Leibniz-Forschungsinstitut für Molekulare Pharmakologie (FMP) have succeeded in revealing a key mechanism of membrane deformation.

“This mechanism plays a fundamental role in cell entry of receptors and hormones and is hijacked by viruses and bacteria,” explains Professor Dr Frank Noé, a computational scientist at Freie Unversität Berlin, who together with Professor Dr Volker Haucke, a biochemist at the FMP, led the study.

High performance computer simulations paired with super-resolution imaging and cell biological methods were the key to the discovery. The work concludes a long-standing quest to complete the understanding of the clathrin mediated endocytosis (CME) pathway and is of high biomedical and biotechnological relevance for the fight against diabetes or cancer and for the development of new antiviral drugs or antibiotics.

“Cells communicate with each other and their environment by receptors displayed on their surface,” explains Prof Dr Frank Noé.

Modulating the number of a particular receptor in the cell’s membrane sets the threshhold for the cell’s sensitivity to the receptor ligand. Some receptors also require being taken up into the cell interior to elicit the correct signals that instruct the cellular response.

“The question here is, how receptor molecules can be internalised into the cell resulting in their removal from the cell membrane,” says Dr Volker Haucke.

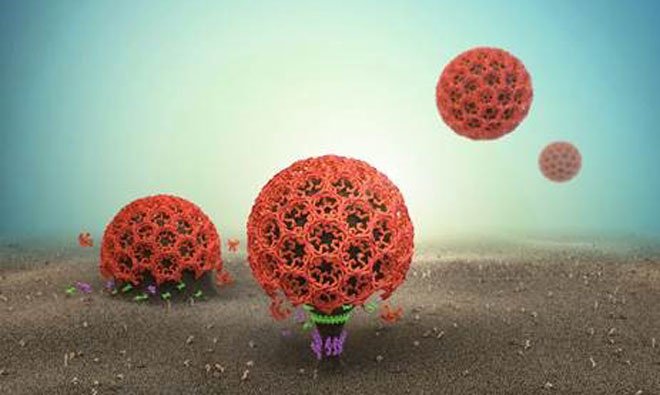

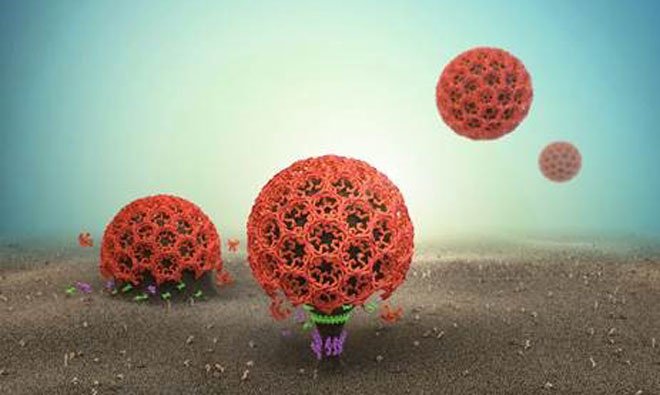

One possibility is to pack them together in a small membrane patch coated by the protein clathrin and then pull the patch back into the cell. This mechanism is called clathrin-mediated endocytosis (CME).

“What happens there is similar to forming a small balloon, a so-called vesicle, in the middle of a large cloth,” says the molecular pharmacologist. First, a cup needs to be formed, then the neck that connects this cup to the cell membrane has to be constricted, and finally cut off with scissors. Scientists know in great detail how molecules form the membrane cup and how scissor molecules eventually cut the neck.

The scientists have now succeeded in finding the missing link: SNX9, the molecule that constricts the neck before it can be cut.

The researchers started by looking for the molecular signal that initiates the neck constriction. “It turned out that during formation of the membrane cup not only the shape of the membrane but also its composition changes,” explains Dr Johannes Schöneberg, one of lead authors of the work.

As the membrane cup grows larger, a particular lipid becomes enriched in it. “One can imagine the site of the process like a molecular concert venue when the main act is playing – it’s very crowded,” says co-first author Dr Martin Lehmann.

The scientists tested a set of candidates and identified SNX9 as the key molecule that can capitalise on the crowding and react strongest to the membrane composition change.

Once identified, the researchers were able to add fluorescent labels to the molecules and witness them remodelling the membrane. The membrane grows into cups and just at the right moment, SNX9 arrives at the neck to tighten right it before it is cut to release a vesicle.

Related topics

Analysis, Antibiotics, Antibodies, Antiretroviral therapies, Biopharmaceuticals, Ligands

Related organisations

Freie Universität Berlin, Leibniz-Forschungsinstitut für Molekulare Pharmakologie