Potential new drug target for polycystic kidney disease

Posted: 28 June 2016 | Victoria White, Digital Content Producer | No comments yet

Researchers have used virtual tissue technology to identify a potential new drug target in the fight against polycystic kidney disease…

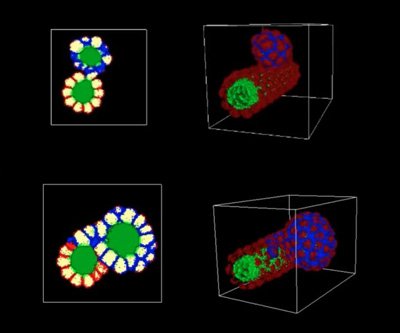

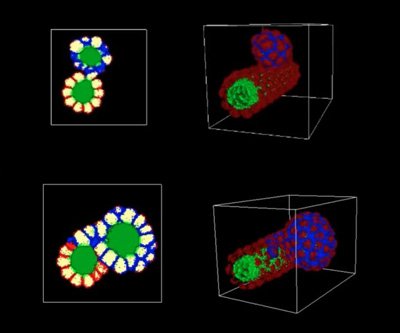

The upper images show two views of the mushroom-shaped cysts that result from the loss of cell adhesion in the nephron. The lower images show the formation of cysts that spread across the surface of the nephron like plaque due to the loss of contact inhibition. CREDIT: Indiana University

Researchers at Indiana University have identified a potential new drug target in the fight against polycystic kidney disease.

Their study reveals that errors in how cells stick together give rise to two forms of kidney cysts.

“This is the first study to show the actual cell behaviours caused by mutations in genes causally linked to polycystic kidney disease, an important new step in the path towards treatment,” said Dr Robert L. Bacallao, associate professor of medicine at the IU School of Medicine in Indianapolis.

The virtual tissue technology used in the study was developed by the Biocomplexity Institute at the IU School of Informatics and Computing, directed by James A. Glazier, professor in the IU Bloomington Department of Intelligent Systems Engineering..

“Not many medical researchers are employing virtual tissue technology,” Glazier explained. “The majority of researchers who use these simulations are pursuing basic science. So it’s extremely exciting to apply the technology to research directed at identifying drug targets to help people suffering from a specific disease.”

To conduct the study, Glazier’s team took data from Bacallao’s medical research to develop a virtual nephron using an open-source software program. The computer model, called CompuCell3D, simulated cell activity triggered by mutations in PKD1 and PKD2, the genes implicated in polycystic kidney disease.

Two types of cysts

The simulations revealed that two types of changes to the cells in these nephrons can results in cysts, both related to how cells stick together. Cells can fail to stick together sufficiently, referred to as reduced cell adhesion, or they can stick together normally but not respond in the correct way to that contact, referred to as a loss of contact inhibition.

Cysts that resulted from reduced cell adhesion were mushroom-shaped, with a stalk and a cap that comprised the bulk of the cyst. Cysts that resulted from loss of contact inhibition proliferated like plaques along the walls of the nephron, then buckled to form “disorganised” cysts. Both types of growth can be seen in video animations generated by the CompuCell3D software.

After running the simulations at IU Bloomington, Bacallao confirmed the cyst growth predictions seen in the virtual cysts in experiments using real human cells cultivated from polycystic kidneys from patients at the IU School of Medicine.

“The computer predictions were absolutely correct,” said Bacallao, who estimated that the same experiments, which took several weeks, would have required 10 to 20 years to conduct in mice.

The study is also the first to confirm the existence of two types of cysts in polycystic kidney disease. The only previous reference to two types of cysts appeared in a largely forgotten description of the dissection of polycystic kidneys in 1972, Bacallao said.

“Now that we know that we’re looking at two different types of cyst that develop in two different ways, we will refine the computer modelling to identify the specific molecular signals leading to each type of cyst,” Glazier said.

Related topics

Drug Targets, Informatics, Virtual tissue technology

Related conditions

Kidney disease

Related organisations

Indiana University