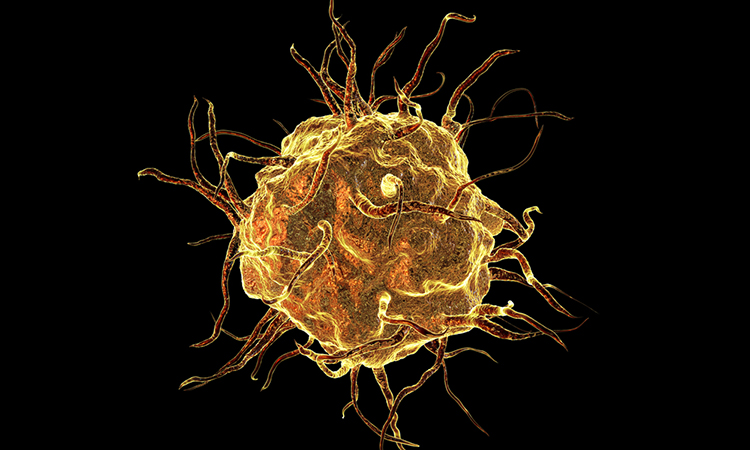

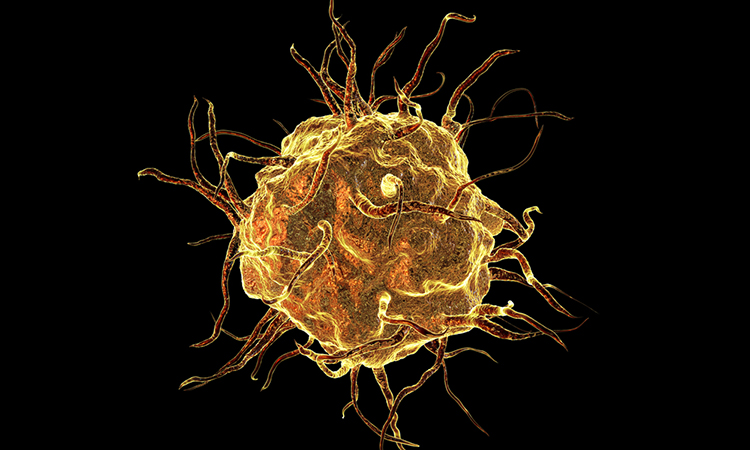

Role of macrophages in blood flow regulation after tissue damage revealed

Posted: 26 April 2021 | Victoria Rees (Drug Target Review) | No comments yet

Researchers have shown in mice that macrophages play a role in controlling blood flow and healing following tissue damage.

Researchers have discovered that one of the most common immune cells in the human body, macrophages, play an important role in re-establishing and controlling blood flow, something that can be used to develop new drugs for conditions such as cardiovascular disease. The study was conducted at Uppsala University, Sweden.

According to the researchers, cardiovascular disease is the result of oxygen deprivation as blood perfusion to affected tissue is prevented. To halt the development of the disease and to promote healing, re-establishment of blood flow is crucial.

The classic function of immune cells is to defend the body against attacks from micro-organisms and tumour cells. Macrophages are immune cells specialised in killing and consuming micro-organisms but they have also been shown to be involved in wound healing and building blood vessels.

The new study demonstrated that macrophages accumulate around blood vessels in damaged tissue in mice, but also in humans after a myocardial infarction or peripheral ischemia. In mice, these macrophages could be seen to regulate blood flow, performing a necessary damage-control function. In healthy tissue, this task is carried out by blood vessel cells.

This discovery led the research group to investigate whether their findings could be developed into a new treatment to increase blood flow to damaged leg muscles, thus stimulating healing and improving function.

Macrophages (green) accumulate around blood vessels in damaged tissue to regulate blood flow [credit: David Ahl].

By increasing the local concentration of certain signal substances that bind to macrophages in the damaged muscle, the group was able to demonstrate that more macrophages accumulated around the blood vessels, improving their ability to regulate blood flow. This in turn resulted in improved healing and the mice were able use the injured leg to a far greater extent.

“This is an entirely new function for the cells in our immune system and might mean that in future we can use immunotherapies to treat not only cancer but also cardiovascular diseases,” said Mia Phillipson, leader of the research group.

The study was published in Circulation Research.

Related topics

Disease research, Drug Development, Immunotherapy, Molecular Targets

Related conditions

Cardiovascular disease, myocardial infarction, Peripheral ischemia

Related organisations

Uppsala University

Related people

Mia Phillipson