Tc24 protein could hold the key to fighting Chagas disease

Posted: 9 December 2015 | Victoria White | No comments yet

Researchers have identified the molecule, Tc24, that is expressed by Trypanosoma cruzi and may facilitate the parasite’s evasion of the host’s immune system…

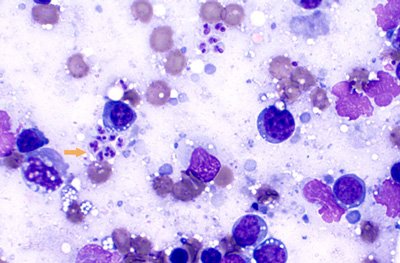

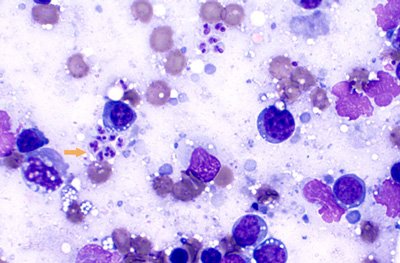

Researchers have identified a molecule expressed by Trypanosoma cruzi (T. cruzi) that may facilitate the parasite’s evasion of the host’s immune system.

T. cruzi causes Chagas disease (also known as American trypanosomiasis) – a disease that affects more than 8 million people across the world. Triatomine bugs, also known as a kissing bug, transmit the T. cruzi parasite. Most human infections come from contact with the faeces of an infected kissing bug, usually after it has bitten a person, although congenital, bloodborne, foodborne and waterborne transmission can occur. Kissing bugs received their name because they usually bite people near their mouth while they sleep.

The researchers, from The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth) School of Public Health, in collaboration with the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, have described a protein, Tc24, that T.cruzi likely uses to hide from the immune system, allowing it to persist for decades undetected until it is too late.

“Thirty percent of infected individuals develop chronic Chagas disease that can result in cardiomyopathy that is untreatable,” said Eric L. Brown, Ph.D., associate professor in the Department of Epidemiology, Human Genetics and Environmental Sciences at UTHealth School of Public Health.

Modifying Tc24 could mount an immune response

Tc24 is a B-cell superantigen that is a member of a family of proteins that can delete populations of B cells capable of secreting antibodies with the ability to neutralise the parasite.

In previous research, Brown found that by slightly chemically modifying superantigens, they are capable of stimulating the immune system rather than suppressing it.

“If we could modify the molecule, we could mount an immune response that would prevent that organism from disseminating and causing infection. This could help both people and canines who are infected with Chagas disease or are at-risk for infection,” said Brown.

In the next phase of research, Brown said he hopes to chemically modify the molecule and conduct preclinical trials to see if the immune-evading process can be reversed.

Related organisations

Texas University