New treatment approach kills lymphoma while sparing healthy cells in mice

Posted: 17 December 2020 | Victoria Rees (Drug Target Review) | No comments yet

By combining natural killer cells with a new molecule called Sialyl-Lewis X, researchers were able to treat lymphoma in mice.

Scientists have demonstrated a promising new strategy for treating lymphomas, a group of cancers that begin in infection-fighting cells of the immune system called lymphocytes. The new approach uses natural cancer-targeting immune cells, known as natural killer (NK) cells, that have been modified to selectively target lymphoma. The study was conducted at Scripps Research, US.

“We found a way to achieve selectivity in targeting lymphoma cells, which is an important departure from existing therapies,” said co-senior author Associate Professor Peng Wu.

According to the researchers, most lymphomas arise from B cells, an important type of lymphocyte whose primary function is to make antibodies. Some existing lymphoma treatments, including B-cell-killing antibodies and so-called CAR T-cell therapies, work by targeting B cells indiscriminately, largely wiping them out. However, this strategy brings many adverse side effects, including months of immunosuppression due to low antibody levels.

Researchers have previously developed a special type of NK cell, NK-92, from a patient with a rare NK-cell cancer. NK-92 cells are relatively easy to grow and multiply in the lab, compared with normal NK cells found in human blood. Since then, NK-92MI cells, an easier-to-multiply version of NK-92 cells, are now being widely investigated for use against various cancers.

In the new study, the team used chemistry techniques to modify NK-92MI cells to concentrate their cancer-fighting power against lymphoma. In an initial set of experiments, the scientists re-engineered NK-92MI cells to include a surface molecule that binds to a B-cell surface receptor called CD22, which is normally abundant on B-cell-derived lymphoma cells. Thus, in principle, the NK-92MI cells would selectively recognise cancerous B cells.

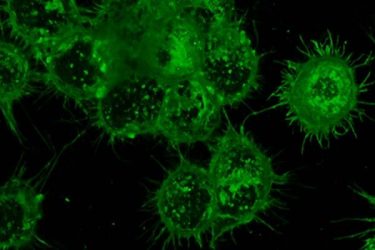

A heavy layer of glycans, seen here in green, cover immune cells and provide a way to target cancer-specific markers in the body [credit: Senlian Hong, Wu Lab at Scripps Research].

In cell-culture tests, the modification brought a big improvement in the NK cells’ ability to kill lymphoma cells and not harm healthy cells. In a mouse model of lymphoma, however, the strategy did not work so well, because the NK cells still did not go where they were needed.

“We found that after being injected, these NK cells tend to be found in the lungs and throughout the bloodstream – whereas in this mouse model and in human lymphoma patients, the lymphoma cells are mostly in the bone marrow,” Wu said.

The team then added to their NK cells a new molecule called Sialyl-Lewis X, which made the cells gather in bone marrow amid the lymphoma cells. This led to a dramatic delay in the development of lymphoma in the mice. With this promising result, the researchers are now continuing to develop this and related strategies for clinical use.

Wu noted that Sialyl-Lewis X, which made the NK-92MI cells gather in bone marrow, as well as the CD22-binding molecule that directed the cells to malignant B cells, are both sugar-like “glycan” molecules. Although such molecules are found on virtually all cells and often have essential biological functions as well as crucial roles in disease, they are difficult to study and thus have been relatively neglected.

The study was published in Angewandte Chemie.

Related topics

Drug Development, Drug Targets, Immunooncology, Immunotherapy, Research & Development, Target molecule

Related conditions

lymphoma

Related organisations

Scripps Research

Related people

Associate Professor Peng Wu