Down syndrome study reveals potential leukaemia drug targets

Posted: 9 September 2020 | Hannah Balfour (Drug Target Review) | No comments yet

The study evaluating Down syndrome endothelial cells presented novel drug targets for leukaemia and suggested why DS patients may be at greater risk from the cancer.

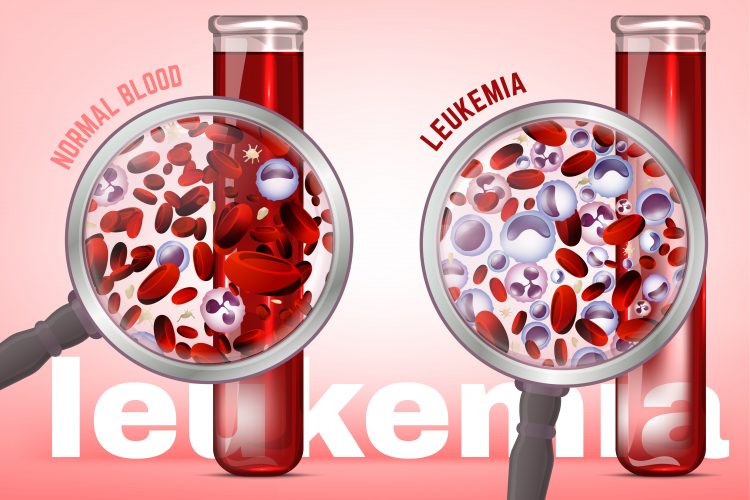

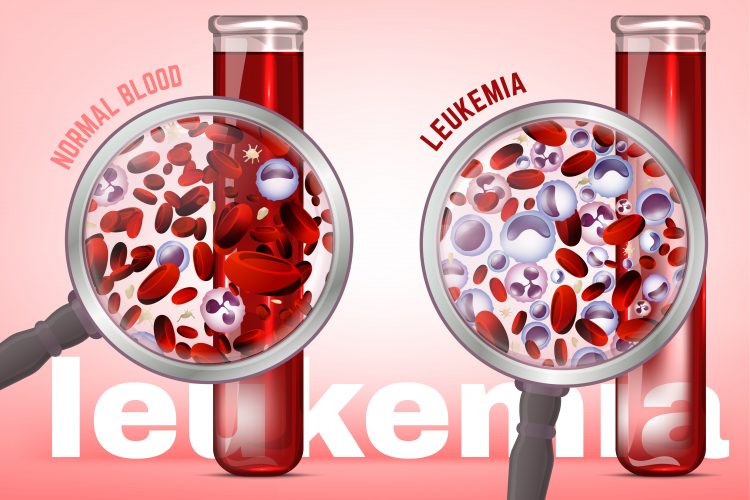

Comparison of normal and leukaemic blood - leukaemia results in blood with a larger proportion of white blood cells and fewer red blood cells.

Researchers exploring how genetic alterations caused by Trisomy 21 (Down Syndrome [DS]) may cause a higher prevalence of leukaemia have identified potential novel drug targets that could be pursued in the treatment of the blood cancer in both DS patients and others in the general population.

Scientists from Stanley Manne Children’s Research Institute at the Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, US, examined endothelial cells – a cell type which produces blood – to identify why people with DS have higher prevalence of leukaemia. They identified a set of genes which is overexpressed in the endothelial cells of patients with DS which may be creating an environment conducive to leukaemia (allowing the uncontrolled development and growth of blood cells). Their findings were published in Oncotarget.

“We found that Down syndrome, or Trisomy 21, has genome-wide implications that place these individuals at higher risk for leukaemia,” said co-lead author Mariana Perepitchka, Research Associate at the Manne Research Institute. “We discovered an increased expression of leukaemia-promoting genes and decreased expression of genes involved in reducing inflammation. These genes were not located on chromosome 21, which makes them potential therapeutic targets for leukaemia even for people without Down syndrome.”

DS is a congenital genetic disorder caused by an additional copy of chromosome 21 (hence the name Trisomy 21 – three copies of chromosome 21). The condition occurs in approximately one in 700 babies and causes developmental and physical impairments. Additionally, people with Down syndrome have a 500-fold risk of developing acute megakaryoblastic leukaemia (AMKL) and a 20-fold risk of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) diagnosis.

In their study, the team took skin samples from patients with Down syndrome and created induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) which then differentiated into endothelial cells. The researchers found that endothelial cells developed from people with Down syndrome exhibited decreased proliferation, reduced migration and a weak TNF-α inflammatory response. Their study highlighted that the phenotype of these patients is characterised by angiogenic, extracellular membrane (ECM)-associated and immune response imbalances, all of which are employed by tumours to create a favourable environment for their growth and metastasis.

The paper suggests the function of these endothelial cells is affected by Trisomy 21 throughout the maturation process and that in DS patient-derived endothelial cells all leukaemia-related oncogenes were upregulated, while oncogenes for solid tumours were downregulated.

They concluded that Down syndrome patients may be at greater risk of leukaemia due to three factors:

- decreased proliferative and migratory capability

- a potentially prolonged inflammatory state; and

- an up-regulation of genome-wide leukaemia-associated oncogenes.

“Fortunately, advances in iPSC technology have provided us with an opportunity to study cell types, such as endothelial cells, that are not easily attainable from patients,” said study senior author, Dr Vasil Galat, Director of Human iPS and Stem Cell Core at Manne Research Institute and Research Assistant Professor of Pathology at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine. “If our results are confirmed, we may have new gene targets for developing novel leukaemia preventions and treatments.”

Related topics

Cell-based assays, Disease research, Drug Targets, Genomics, Oncology

Related conditions

acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL), Acute megakaryoblastic leukaemia (AMKL), Down syndrome, Leukaemia

Related organisations

Stanley Manne Children's Research Institute

Related people

Dr Vasil Galat, Mariana Perepitchka