Antisense oligonucleotides used to treat prion disease in animal models

Posted: 11 August 2020 | Victoria Rees (Drug Target Review) | No comments yet

Researchers have shown that using antisense oligonucleotides to reduce the levels of prion protein in lab animals with prion disease can extended their survival.

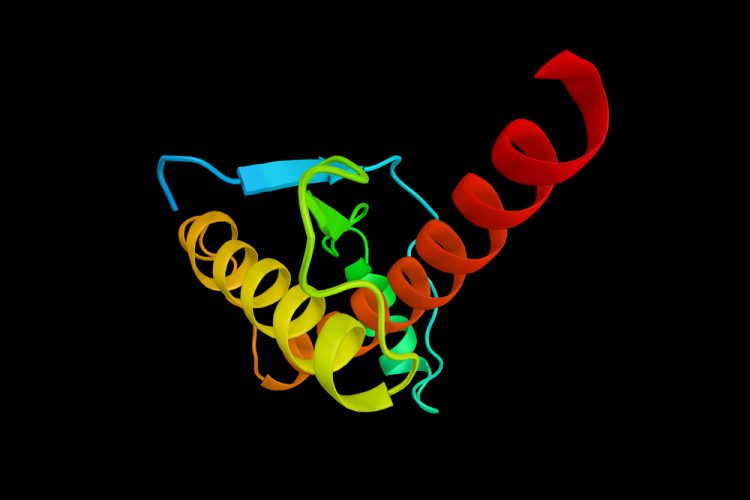

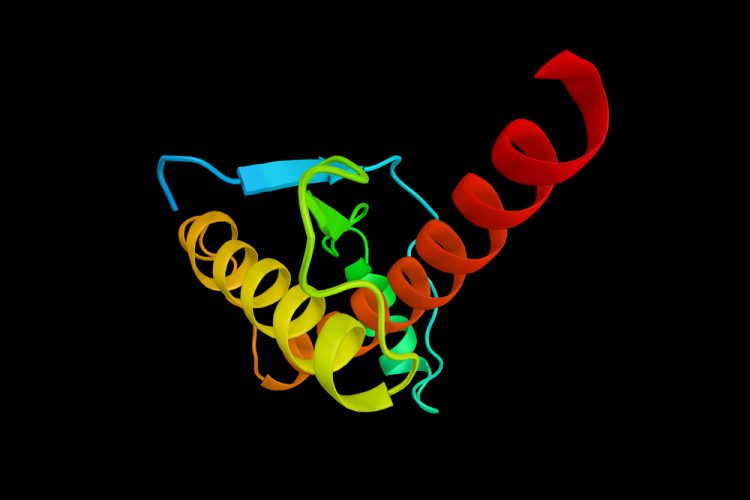

Prion protein.

A new study has suggested a possible effective treatment strategy for patients suffering from prion disease, a rapidly fatal and currently untreatable neurodegenerative disease.

Teams led by Sonia Vallabh at the Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT, both US, Holly Kordasiewicz at Ionis Pharmaceuticals and Deb Cabin at McLaughlin Research Institute, US, report the results of pre-clinical studies of an antisense therapy against prion disease.

According to the researchers, prion diseases are caused by disrupting the structure of a normal human prion protein, producing toxic clumps in the brain. As the protein is central to disease, they say that reducing levels of prion protein in patients is a promising therapeutic approach.

Senior author Vallabh and her coworkers had previously observed that antisense oligonucleotides that reduce levels of prion protein can extend the survival of animals infected with misfolded prions.

In their new study, they used an expanded set of prion protein-targeting antisense oligonucleotides to lay the basis for full scale clinical development. This research shows that, across multiple treatment paradigms, reducing levels of prion protein in prion-infected lab animals significantly extended their survival.

The researchers discovered that decreasing the levels of prion protein can triple the survival of prion-infected animals. Even reducing prion protein levels by a small amount, which should be easier to achieve clinically, resulted in significant survival benefits.

They found that reducing the prion protein is also effective before any symptoms can be seen. Furthermore, they demonstrated, for the first time, that a single dose of a prion protein-lowering treatment can reverse markers of disease even after toxic clumps have formed in the brain in animal models.

“While there are still many steps ahead,” said Vallabh, “these data give us optimism that by aiming straight at the genetic heart of prion disease, genetically targeted drugs designed to lower prion protein levels in the brain may prove effective in the clinic.”

The results can be found in Nucleic Acids Research.

Related topics

Drug Targets, Prions, Protein, Proteomics, Research & Development, Target molecule, Targets

Related conditions

Prion diseases

Related organisations

Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Ionis Pharmaceuticals, McLaughlin Research Institute

Related people

Deb Cabin, Holly Kordasiewicz, Sonia Vallabh