New generation of CAR T cells developed

Posted: 6 December 2019 | Hannah Balfour (Drug Target Review) | No comments yet

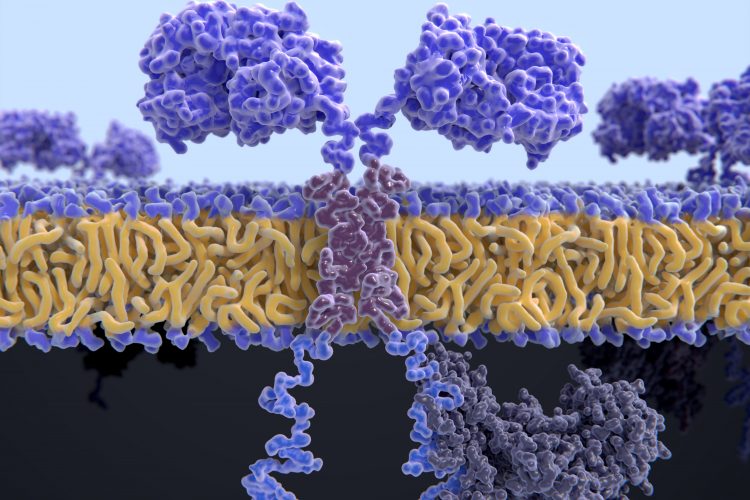

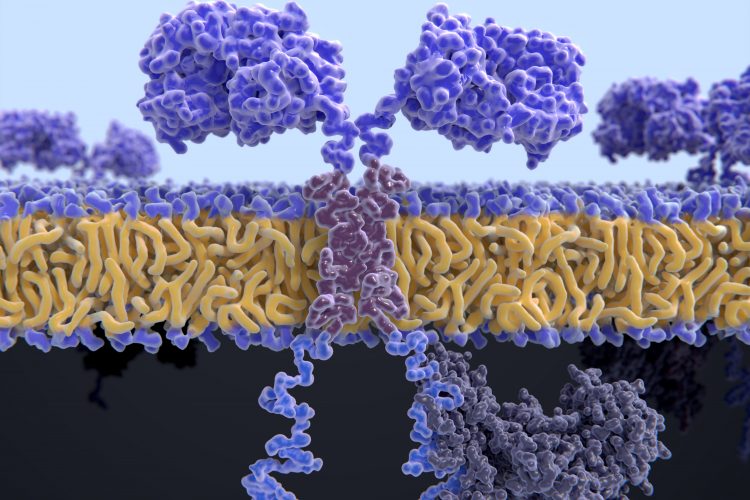

Researchers have reprogrammed CAR T cells to prevent them becoming exhausted after prolonged activity, presenting a possible new therapy for solid tumours.

Researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine, US have found a new approach to programming chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells, prolonging their activity and increasing their effectiveness against human cancer cells grown in the laboratory and in mice.

Despite blood cancers responding well to CAR-T treatment, fewer than half of treated patients experience long-term control of their disease. This is attributed to the cells becoming exhausted, losing their ability to proliferate robustly and no longer actively attacking cancer cells, leading scientists to search for a way to overcome this complication.

…researchers found that the cells remained active and proliferated in the laboratory even under conditions that would normally result in their exhaustion”

“We know that T cells are powerful enough to eradicate cancer,” said Dr Crystal Mackall, senior author of the study, professor of paediatrics and of medicine at Stanford and the associate director of the Stanford Cancer Institute. “But these same T cells have evolved to have natural brakes that tamp down the potency of their response after a period of prolonged activity. We’ve developed a way to mitigate this exhaustion response and improve the activity of CAR T cells against blood and solid cancers.”

Mackall and former postdoctoral scholar Dr Rachel Lynn, the lead author of the study, used a technique called ATAC-Seq to pinpoint areas of the genome where regulatory circuits overexpress or under-express genes.

“When we used this technique to compare the genomes of healthy and exhausted T cells, we identified some significant differences in gene expression patterns,” explained Mackall. They highlighted that exhausted T cells demonstrate an imbalance in the activity of a major class of genes regulating protein levels in the cells. The disparity causes an increase in proteins that inhibit T-cell activity.

By modifying CAR T cells by overexpressing c-Jun, a gene that increases the expression of proteins associated with T-cell activation, researchers found that the cells remained active and proliferated in the laboratory even under conditions that would normally result in their exhaustion.

Researchers treated mice that had been injected with human leukaemia cells with the modified CAR T cells and found that they lived longer than those treated with regular CAR T cells. In addition, the c-Jun expressing CAR T cells were also able to reduce the tumour burden and extend the lifespan of laboratory mice with a human bone cancer called osteosarcoma.

“Those of us in the CAR T-cell field have wondered for some time if these cells could also be used to combat solid tumours,” Mackall said. “Now we’ve developed an approach that renders the cells exhaustion resistant and improves their activity against solid tumours in mice. Although more work needs to be done to test this in humans, we’re hopeful that our findings will lead to the next generation of CAR T cells and make a significant difference for people with many types of cancers.”

The findings were published in Nature.

Related topics

Bioengineering, Chimeric antigen receptors (CARs), Drug Development, Drug Targets, Oncology, Protein Expression, Research & Development, t-cells

Related conditions

blood cancers, bone cancer, Leukaemia, osteosarcoma, solid tumours

Related organisations

Stanford Cancer Institute, Stanford University School of Medicine

Related people

Dr Crystal Mackall