Microglia critical for neurodegeneration in mice, study finds

Posted: 14 October 2019 | Victoria Rees (Drug Target Review) | No comments yet

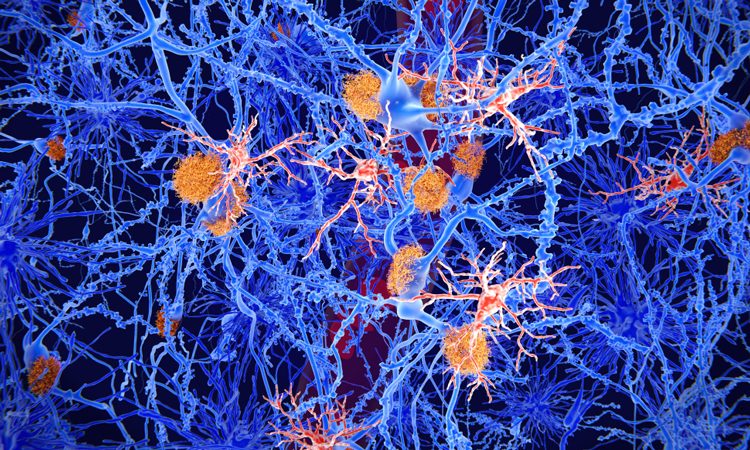

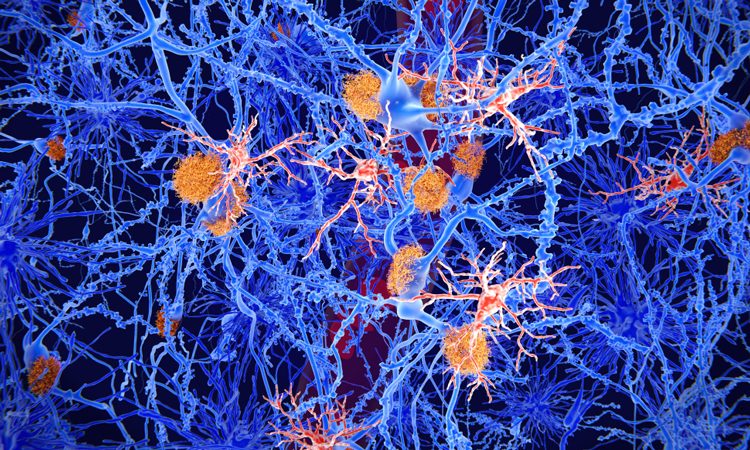

Microglia brain immune cells are vital in conjunction with the APOE4 gene during the development of Alzheimer’s in mouse models, researchers have found.

A study has revealed that microglia brain immune cells, activated when tau tangles accumulate, form the crucial link between protein clumping and brain damage. The researchers demonstrated that eliminating these cells reduced tau-linked damage in mice, providing a potential therapeutic pathway for Alzheimer’s disease.

The team, from the Washington University School of Medicine, US, have previously shown that microglia limit the development of a harmful form of tau. However, they suspected that once the tau tangles have formed, the cells’ attempts to attack them may harm nearby neurons and contribute to neurodegeneration.

…the brains of mice that had their microglia eliminated appeared normal and healthy”

Genetically modified mice which carry a mutant form of human tau that easily clumps together were utilised. The researchers used the models to investigate the APOE gene; people who carry the APOE4 variant are up to 12 times more likely to develop Alzheimer’s than other variants. The mice either carried the human APOE4 gene or no APOE gene.

The models were fed with either a compound to deplete microglia in their brains or a placebo.

The brains of mice with tau tangles and the APOE4 gene were severely shrunken and damaged when microglia were present. Conversely, the brains of mice that had their microglia eliminated appeared normal and healthy with less evidence of harmful forms of tau, despite the presence of APOE4.

Also, mice with microglia and the mutant human tau but no APOE had minimal brain damage and fewer signs of damaging tau tangles. Further study revealed that microglia need APOE to become activated and when not activated, do not destroy brain tissue or promote harmful forms of tau.

“Microglia drive neurodegeneration, probably through inflammation-induced neuronal death,” said first author Dr Yang Shi. “But even if that’s the case, if you don’t have microglia, or you have microglia but they can’t be activated, harmful forms of tau do not progress to an advanced stage and you don’t get neurological damage.”

“If you could target microglia in some specific way and prevent them from causing damage, I think that would be a really important, strategic, novel way to develop a treatment,” said senior author Professor David Holtzman.

The results were published in the Journal of Experimental Medicine.

Related topics

Disease research, Drug Targets, microglial cells, Neurosciences, Research & Development

Related conditions

Alzheimer’s disease

Related organisations

Washington University School of Medicine

Related people

Dr Yang Shi, Professor David Holtzman