Research identifies cells which contribute to inflammatory diseases

Posted: 21 June 2019 | Victoria Rees (Drug Target Review) | No comments yet

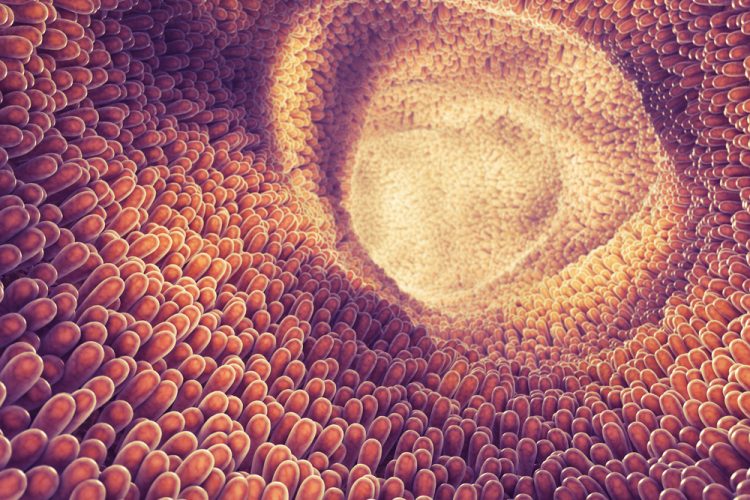

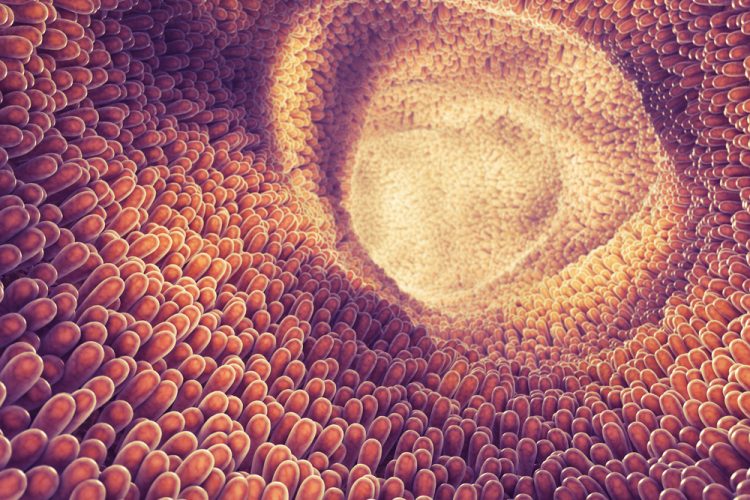

A new study has shown that there are two populations of cells in the gut which leads to drug development potential.

A recent study has characterised two distinct populations of gut immune cells, with differing roles in the body. The two parts they play has led the researchers to suggest new drug design developments for Crohn’s Disease and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

The team of researchers, at Crick, UK, and King’s College London investigated T helper 17 (Th17) cells, which have a known role in inflammatory disorders but also help to keep the gut lining healthy. The cells which fight infection travel from lymph nodes to the gut and other parts of the body to attack invading pathogens. Although necessary to fight infection, these cells can cause inflammation. Previous studies have failed to make the distinction between the two populations.

“Th17 cells clearly have many roles in the body – and we need them to fight off infection and keep our intestines healthy,” says Gitta Stockinger, Crick group leader and senior author of the paper. “Any treatment for inflammatory disease would need to dampen the abnormal attack of Th17 cells on healthy tissues, without causing digestive complications or an inability to fight off germs.”

In the study, researchers investigated Th17 cells in mice which were activated by either harmless microbes normally present in the gut (gut flora), or an intestinal pathogen equivalent to a type of E. coli in humans. The mice were genetically modified so that activated Th17 cells were fluorescently labelled.

The gut flora-activated Th17 cells kept their function as a protective barrier and did not cause inflammation. Comparatively, the pathogen-activated Th17 cells released inflammatory signals and caused widespread inflammation.

The team infected gut flora-activated Th17 mice with the pathogen and used a drug to block any new Th17 cells from moving to the gut. The Th17 cells analysed were non-inflammatory, confirming that the resident Th17 are distinct from pathogen-activated Th17 cells. However, blocking the invasion of the fighter Th17 cells into the gut prevented the mice from successfully fighting off the infection.

“Our findings may help ensure that future therapies for inflammatory diseases that target these cells do not inadvertently damage the resident intestinal population important for gut health,” continued Stockinger.

The findings were published in Immunity.

Related topics

Drug Development, Drug Targets, Research & Development

Related conditions

Crohn’s disease, inflammatory bowel disease

Related organisations

Crick, Immunity, King's College London

Related people

Gitta Stockinger