Rare mechanism for ALL to relapse after CAR-T therapy

Posted: 2 October 2018 | Iqra Farooq (Drug Target Review) | No comments yet

A single leukemic cell has become resistant to CAR-T therapy after unknowingly engineered with the leukemia-targeting CAR lentivirus…

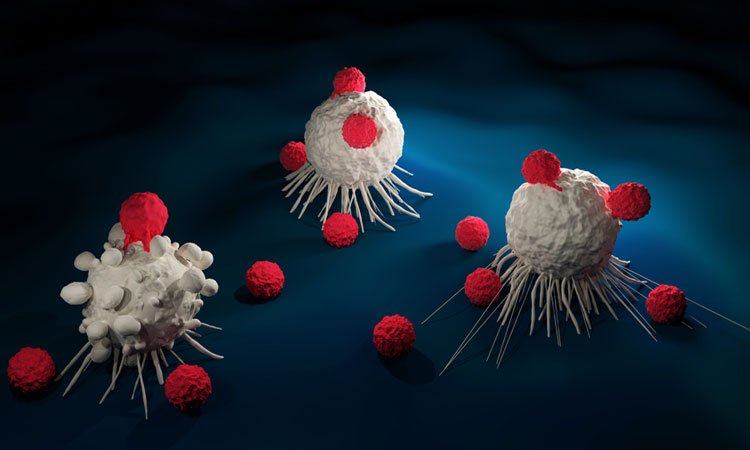

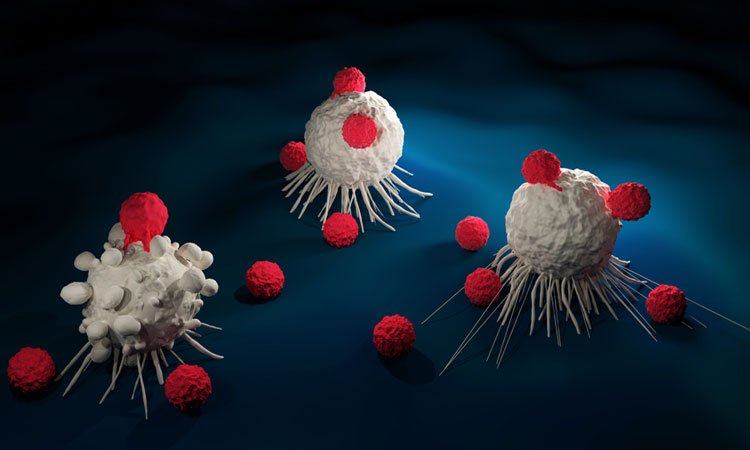

One leukaemia cell was able to reproduce and cause a deadly recurrence of B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, when unknowingly engineered with the leukemia-targeting chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) lentivirus and infused back into a patient.

Researchers from the Abramson Cancer Center of the University of Pennsylvania found that in one patient the CAR lentivirus that ordinarily enters a T-cell to teach it to hunt cancer, also became bound to a leukemic cell.

The presence of the CAR on the leukemic cell could have enabled the cell to ‘hide’ from the therapy by masking CD19 – the protein targeted by the CARs to kill cancer. Leukemic cells without CD19 are resistant to CAR T therapy, so this single cell led to the patient’s relapse.

The treatment was developed by researchers at the Perelman School of Medicine and at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) modifies the patients own T-cells, collecting and reprogramming them to seek and destroy their own cancer cells.

Once they are back into the patients’ body, they multiply and attack cancer cells that express CD19.

“In this case, we found that 100 percent of relapsed leukemic cells carried the CAR that we use to genetically modify T cells,” said the study’s lead author Dr Marco Ruella, Assistant Professor of Hematology-Oncology at Penn.

“This is the first time in hundreds of patients treated at Penn and other institutions that we’ve observed this mechanism of relapse, and it provides important evidence that due to the delicate and complex manufacturing process any slight variation can have an impact on patient outcomes.”

The 20-year-old who received the CAR-T cell therapy manufactured by Penn, as part of a sponsored trial, entered with very advanced leukemia that had relapsed three times previously. After receiving the therapy, the the patient had a complete remission for nine months before relapsing.

In about 60 percent of ALL relapses, testing shows cancer cells that do not express CD19, and was also not detectable at relapse in this patient. But in this case, analysis showed the leukemia cells were positive for the CAR protein.

“We learn so much from each patient, in both success or failure of this new therapy, that helps us improve these still-developing treatments so they can benefit more patients,” said Associate Professor J. Joseph Melenhorst.

“This is a single case, but is still incredibly important and can help us refine the intricate processes required for manufacturing CAR-T cell therapy to ensure the best chance of long-term remissions.”

The study was published in Nature Medicine.

Related topics

Disease research, Drug Discovery, Oncology, Research & Development, Therapeutics

Related conditions

Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, Leukaemia

Related organisations

Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), Perelman School of Medicine

Related people

Dr Marco Ruella, Professor J. Joseph Melenhorst