yTRAP used to quantitatively measure and manipulate protein aggregation

Posted: 23 October 2017 | Dr Zara Kassam (Drug Target Review) | No comments yet

Researchers have built a synthetic genetic tool yTRAP to quantitatively sense, measure and manipulate protein aggregation in live cells…

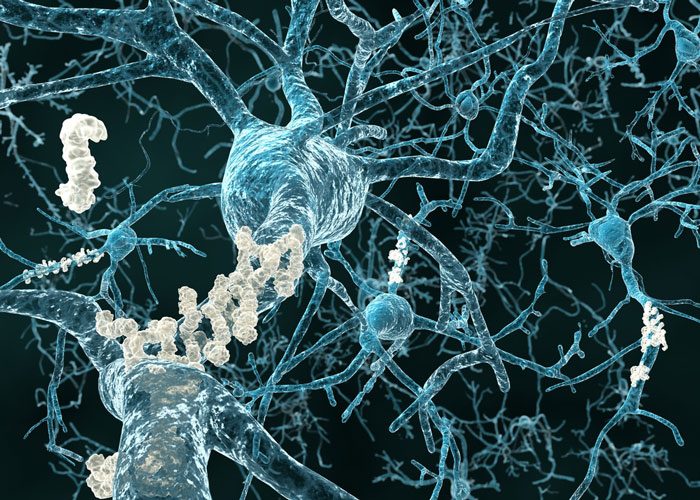

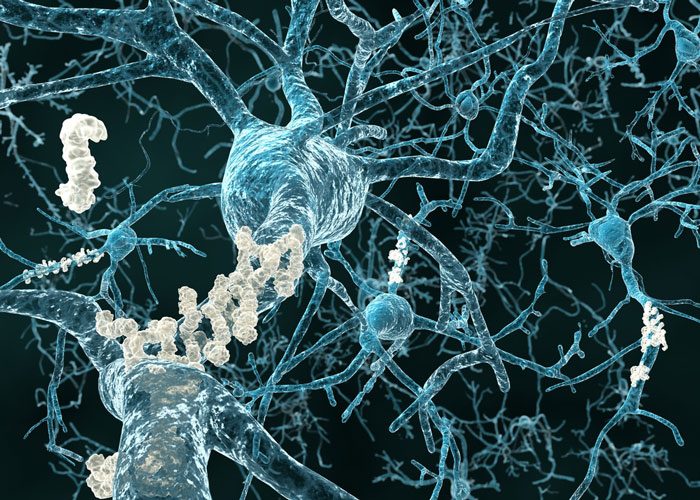

Even though protein aggregation is prevalent in biology, many of the causes and consequences are unknown.

Researchers at Boston University have built a synthetic genetic tool called yTRAP (yeast Transcriptional Reporting of Aggregating Proteins) to quantitatively sense, measure and manipulate protein aggregation in live cells.

Using the new tool, Assistant Professor Ahmad S. Khalil and his research team have created sensors to track aggregation of prions and other proteins, manipulated prions to engineer synthetic memories in cells, identified genes that can cure cells of prions and enabled high-throughput studies to learn what can influence protein aggregation and its consequences.

Although developed and tested in yeast, yTRAP could allow scientists to test and develop treatments for currently incurable diseases and potentially turn on new, beneficial functions in other types of cells.

The tool is composed of two parts–one piece couples to the protein of interest and the other produces a fluorescent signal to measure the amount of aggregation in a cell. Each piece can be customised to study different proteins or express different genes and signals. For example, they were able to measure how one prion influenced another by developing a dual sensor that produced either a red or green fluorescent signal depending on how abundant each prion was.

In addition to tracking prion states, yTRAP can also be used to control those states. Because prions are heritable, once they are triggered in a cell, all of the cells in later generations will inherit the same prion state. “Prions are a biological equivalent of a toggle light switch — you don’t have to keep your finger on the switch to keep the light on,” said Prof Khalil.

They used this light switch-like heritable property of prions to build a synthetic memory device. Heat activated the prion to aggregate in a batch of cells and the hotter it got, the more aggregates formed. Then, 10 generations later, cells that were never exposed to heat maintained the same level of aggregation their predecessors did.

Protein aggregates can cause a cell to gain or lose a function

This synthetic cellular memory device is like installing a dimmer switch onto that light–the brighter the light gets, the more aggregates will form in the cell population. Additionally, the researchers used yTRAP as part of a method to identify genes that could be used to essentially turn prions off, handing researchers the ability to toggle that light switch in the other direction.

Prof Khalil and his team also demonstrated how the tool can be used to study other proteins, including RNA-binding proteins. Many of these proteins in yeast and humans have similarities to prions, and mutations of those similarities have been linked to neurodegenerative diseases like ALS. With the help of the tool, they uncovered aggregation-prone RNA-binding proteins, monitored the consequences of their aggregation and performed high-throughput screens to see how the aggregation of one protein influences another.

“Protein aggregates can cause a cell to gain or lose a function,” said Prof Khalil. “It could be beneficial or harmful. For example, it could allow a cell to survive stressful conditions or change its metabolic function to digest a different type of sugar. And the discovery of these beneficial functions has often been serendipitous.” With yTRAP, Prof Khalil hopes to change that.

All of these functions yTRAP provides will allow researchers to discover new protein aggregates, track their complicated behaviours, and look for factors and drugs that alter protein aggregation as potential treatments for currently incurable neurodegenerative diseases, or, on the flip side, figure out how to turn on a beneficial function of an aggregate. This is due because no simple, standardised research tool exists to study this phenomenon in live cells.

Prions are a special, heritable form of aggregation and are most famous for transmitting neurodegenerative diseases in mammals. But they are also used by organisms to execute a diverse set of beneficial functions that are just starting to be identified.

Related topics

Protein, Proteomics

Related conditions

Alzheimer’s disease

Related organisations

Boston University

Related people

Professor Ahmad S. Khalil