Nanoparticles hold promise in the fight against genital herpes

Posted: 28 April 2016 | Victoria White, Digital Content Producer | No comments yet

Researchers have shown that zinc-oxide nanoparticles can prevent genital herpes virus from entering cells, and help natural immunity to develop…

Researchers have shown that zinc-oxide nanoparticles can prevent genital herpes virus from entering cells, and help natural immunity to develop.

Commenting on the research, Deepak Shukla, professor of ophthalmology and microbiology & immunology in the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) College of Medicine, said: “We call the virus-trapping nanoparticle a microbivac, because it possesses both microbicidal and vaccine-like properties. It is a totally novel approach to developing a vaccine against herpes, and it could potentially also work for HIV and other viruses.”

The researchers say the particles could serve as a powerful active ingredient in a topically-applied vaginal cream that provides immediate protection against herpes virus infection while simultaneously helping stimulate immunity to the virus for long-term protection.

Herpes simplex virus-2, which causes serious eye infections in newborns and immunocompromised patients as well as genital herpes, is one of the most common human viruses. HSV-2 can hide out for long periods of time in the nervous system. The genital lesions caused by the virus increase the risk for acquiring human immunodeficiency virus, or HIV.

Treatments for HSV-2 include daily topical medications to suppress the virus and shorten the duration of outbreaks, when the virus is active and genital lesions are present. However, drug resistance is common, and little protection is provided against further infections. Efforts to develop a vaccine have been unsuccessful because the virus does not spend much time in the bloodstream, where most traditional vaccines do their work.

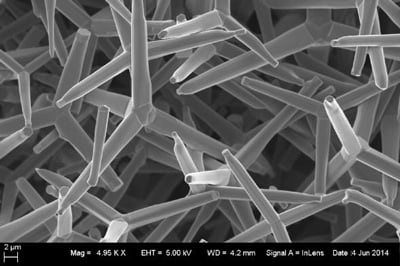

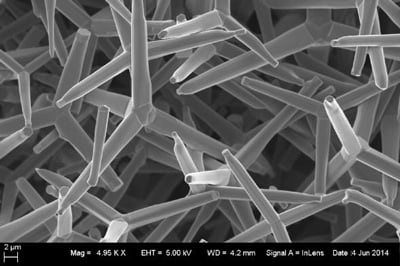

Negatively charged ZOTEN attract the HSV-2 virus

The tetrapod-shaped zinc-oxide nanoparticles, called ZOTEN, have negatively charged surfaces that attract the HSV-2 virus, which has positively charged proteins on its outer envelope. When bound to the nanoparticles, HSV-2 cannot infect cells. But the bound virus remains susceptible to processing by immune cells called dendritic cells that patrol the vaginal lining. The dendritic cells “present” the virus to other immune cells that produce antibodies. The antibodies cripple the virus and trigger the production of customised killer cells that identify infected cells and destroy them before the virus can take over and spread.

The researchers showed that female mice swabbed with HSV-2 and an ointment containing ZOTEN had significantly fewer genital lesions than mice treated with a cream lacking ZOTEN. Mice treated with ZOTEN also had less inflammation in the central nervous system, where the virus can hide.

The researchers were able to watch immune cells pry the virus off the nanoparticles for immune processing, using high-resolution fluorescence microscopy.

“It’s very clear that ZOTEN facilitates the development of immunity by holding the virus and letting the dendritic cells get to it,” Shukla said.

If found safe and effective in humans, a ZOTEN-containing cream ideally would be applied vaginally just prior to intercourse, Shukla said. But if a woman who had been using it regularly missed an application, he said, she may have already developed some immunity and still have some protection. Shukla hopes to further develop the nanoparticles to work against HIV, which like HSV-2 also has positively charged proteins embedded in its outer envelope.

Related topics

Microscopy, Nanoparticles

Related organisations

University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC)