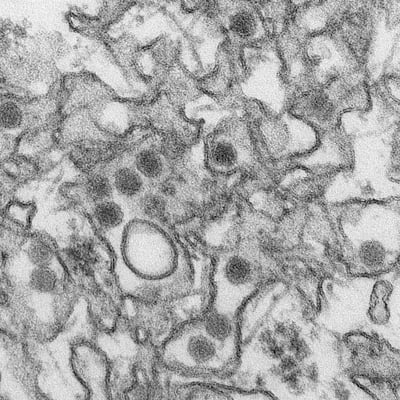

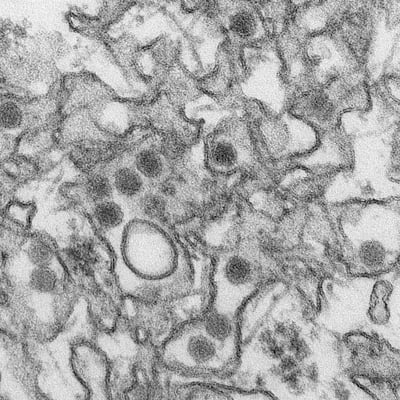

UW-Madison researchers look for ways to stop Zika virus

Posted: 27 January 2016 | Victoria White | No comments yet

Researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and Universidad de Sucre ran the first tests confirming the presence of Zika virus transmission in Columbia. Now they’re looking for ways to control the virus…

In October 2015, a team of researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and Universidad de Sucre ran the first tests confirming the presence of Zika virus transmission in Columbia.

In a new study, the team documents a disease trajectory that started with nine positive patients and has now spread to more than 13,000 infected individuals in that country.

“Colombia is now only second to Brazil in the number of known Zika infections,” says Matthew Aliota, a research scientist in the UW-Madison School of Veterinary Medicine (SVM).

Zika virus, which spreads among humans via mosquitoes, causes illness characterised like many other viral infections by fever, rash and joint pain. Officials estimate that four out of five people who contract the virus do not get sick and the virus is rarely fatal. However, pregnant women in Brazil infected with Zika have given birth to babies with small heads and underdeveloped brains, a condition called microcephaly.

For the Colombian finding, Aliota and his research team, which includes Jorge Osorio, professor of pathobiological sciences at SVM, and two visiting doctoral students from Colombia, tested samples from 22 patients for the genetic fingerprints of Zika, dengue and chikungunya viruses.

Nine came back positive for Zika virus. Now, 13,500 cases have been identified in Colombia. The researchers’ findings highlight the need for better, more accurate laboratory diagnosis of Zika virus.

The symptoms of Zika virus are “really nonspecific and it overlaps with a lot of things, especially with dengue virus and chikungunya,” says Aliota. “It’s hard when someone comes in with a fever and a rash to narrow it down.”

Zika virus was first found in Uganda in 1947 but remained limited to Africa and Southeast Asia for decades. But in 2007, an outbreak occurred in the Pacific Islands and recently the virus began to spread in the Western Hemisphere.

“Historically, Zika virus has just caused mild disease, but as it moved into the New World, in Brazil, we started to notice these more serious consequences associated with it,” says Aliota. “There is a lot that is unknown.”

Aliota’s research on Zika virus focused on how the virus evolves and adapts to its hosts, including mosquitoes and humans. As he and the team show in the study, the Zika virus has split into two distinct lineages, African and Asian. The Colombia strain of the virus can be tracked to Brazil, which can be traced to a strain that originated in French Polynesia.

Researchers investigating if Wolbachia might be used for Zika virus control

He and Osorio are now looking for ways to control the virus. As members of the Eliminate Dengue Programme, they have explored how a bacterium that infects 60% of insects around the world may be used as a tool to combat the spread of dengue, zika and similar mosquito-borne viruses. Zika, dengue and chikungunya are RNA viruses and each is transmitted by a specific mosquito called Aedes aegypti. The bacterium, Wolbachia, is not naturally found in the Aedes aegypti mosquito, but researchers with Eliminate Dengue have found that when they infect mosquitoes with the bacteria in the lab, it prevents them from transmitting dengue, chikungunya and yellow fever.

“The Eliminate Dengue Programme is doing field experiments to see, will we be able to replace wild-type, existing populations of mosquitoes with these Wolbachia-infected ones and does it block dengue transmission?” Aliota says. “Now, we’re going to start looking at how that might be used for Zika virus control as well in South America.”

Related conditions

Zika virus

Related organisations

UW Madison