Immune cell changes detected in Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia (WM)

Posted: 2 September 2021 | Anna Begley (Drug Target Review) | No comments yet

A new study has found mutations originating in blood progenitor cells, possibly leading to Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia (WM) therapies.

A team at Emory University, US, have found that cancer-associated mutations originate in blood progenitor cells, leading to distinct changes in both cancer and non-cancer immune cells in Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia (WM) and its precursor IgM monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS).

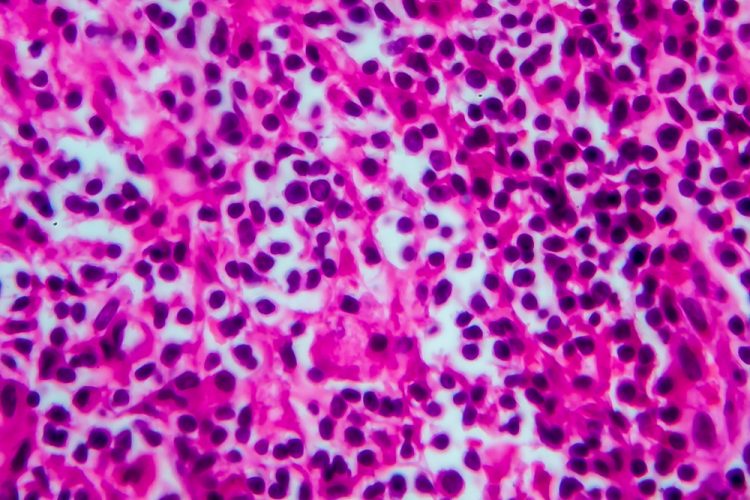

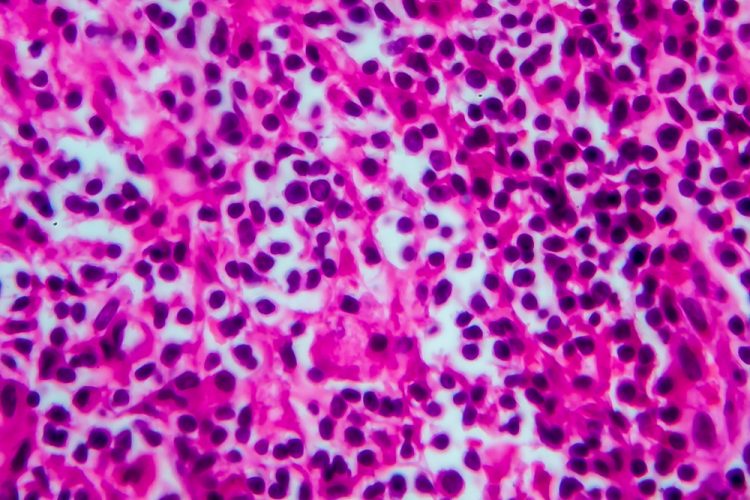

WM, also known as lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma, is the result of growth of cancer cells in the bone marrow producing large amounts of an abnormal protein called a macroglobulin. Most cases of WM are characterised by mutations in the MYD88 gene and the cancerous accumulation of B cells.

“When we applied several high-content profiling approaches to study samples from these patients, we were surprised to find out that not only were tumour cells highly abnormal, but so were non-tumour cells,” explained Professor Kavita Dhodapkar at Emory University. “This led us to suspect that perhaps the mutations are already present in earlier blood progenitors that give rise to both cancer and non-cancer cells.”

Drug Target Review has just announced the launch of its NEW and EXCLUSIVE report examining the evolution of AI and informatics in drug discovery and development.

In this 63 page in-depth report, experts and researchers explore the key benefits of AI and informatics processes, reveal where the challenges lie for the implementation of AI and how they see the use of these technologies streamlining workflows in the future.

Also featured are exclusive interviews with leading scientists from AstraZeneca, Auransa, PolarisQB and Chalmers University of Technology.

Examining individual cells with a combination of high-dimensional approaches and genome sequencing of subpopulations, the researchers showed that WM and its precursor, IgM gammopathy, originate in the backdrop of several alterations in non-cancer cells as well as MYD88 mutations in blood progenitors. According to the team, these alterations include inflammation in the bone marrow, the depletion of naïve B and T cells and an increase in a distinct type of B cells called extrafollicular B cells.

“The data in this paper have several potential implications for origins and therapy of WM,” added Professor Madhav Dhodapkar. “They provide an example of how cancer-associated mutations can impact not just the cancer cells, but also non-cancer cells in the tumour milieu. They also provide evidence for host immune system to tackle these lesions, which may lead to new immune therapies.”

The study was published in Blood Cancer Discovery.

Related topics

Drug Leads, Genetic analysis, Genomics, In Vitro, Oncology, t-cells, Targets

Related conditions

Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia

Related organisations

Emory University

Related people

Professor Kavita Dhodapkar, Professor Madhav Dhodapkar