Metabolite could defend against harmful intestinal bacteria, study shows

Posted: 21 July 2021 | Anna Begley (Drug Target Review) | No comments yet

Acetate was found to be involved in regulating complex microbes and could help trigger an immune response against harmful bacteria in mice.

Researchers at the RIKEN Center for Integrative Medical Sciences (IMS), Japan, have found that acetate is in involved in regulating microbes in the intestine. Importantly, their experiments showed that acetate could trigger an immune response against potentially harmful bacteria which could lead to the development of novel ways to regulate the balance of intestinal bacteria.

Recent studies have suggested that short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), a major metabolite of intestinal bacteria, are involved in creating and regulating immune-cell function. Studies have also shown that SCFAs could increase immunoglobulin A (IgA), an antibody that is thought to regulate growth, colonisation and function of intestinal bacteria by binding to them. However, scientists did not know what could trigger IgA responses to bacteria in a dynamically changing environment.

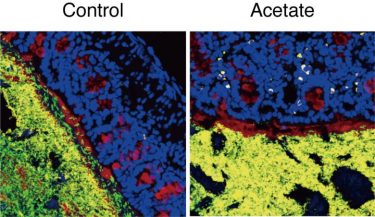

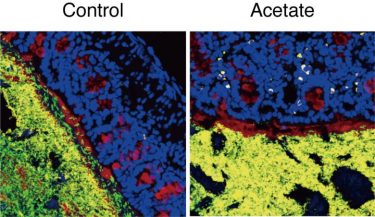

Acetate increased IgA production (yellow). IgA bound to potentially harmful bacteria (green) and prevented them from invading the mucus layer (red) [credit: RIKEN].

The team, led by Hiroshi Ohno, fed mice food that can specifically increase SCFAs locally in the large intestine. Analysis of the mice showed that acetate, a type of SCFA, increased both the number of IgA-producing cells and the amount of IgA. It also regulated how much IgA was bound to each intestinal bacterium. Other SCFAs, such as propionic acid or butyric acid, did not affect IgA.

“SCFAs including acetate are easily absorbed in the stomach and proximal small intestine, so it was difficult to investigate the effects of orally administered SCFAs in the distal intestine such as the colon, where the intrinsic SCFA levels are high,” said Ohno. “Our collaborators have developed a method that can efficiently deliver metabolites into the distal intestine, which enabled us to analyse the effects of SCFAs on the immune system there.”

The team also found that the type of bacteria to which IgA binds depends on whether acetate is present or not. Usually, IgA binds to common symbiotic bacteria, but in mice treated with acetate, it tended to bind to potentially harmful bacteria such as E. coli. More detailed analysis showed that when acetate leads to IgA production in the colon, the IgA binds to those potentially harmful bacteria and prevents them from settling in and invading the mucus layer.

“At first we thought that acetate simply increases IgA equally against all commensal bacteria,” Ohno continued. “It was rather surprising to see that it preferentially enhances production of IgA against certain microbes through collaboration with other immune cells.” In fact, the experiments revealed that acetate only increased IgA production when potentially harmful bacteria were present.

Ohno concluded: “Accumulating evidence suggests the involvement of gut microbiota in many human diseases… Since the functions of metabolites remain largely unknown, we will keep focusing on host-microbe interactions through these small molecules to reveal how they affect human pathophysiology.”

The findings were published in Nature.

Related topics

Immunology, In Vivo, Metabolomics, Microbiology, Microbiome, Molecular Biology

Related organisations

RIKEN Center for Integrative Medical Sciences (IMS)

Related people

Hiroshi Ohno