Microptosis could present an antimicrobial drug development opportunity

Posted: 20 January 2016 | Victoria White | No comments yet

Researchers have described a novel pathway called microptosis where the immune system’s killer cells deliver a 3-phase knockout punch that kills intracellular parasites…

Researchers at Boston Children’s Hospital have reported a novel pathway called “microptosis” where the immune system’s killer cells deliver a tightly controlled, 3-phase knockout punch that kills intracellular parasites.

The investigators say this pathway is very similar to apoptosis but with subtle differences suggesting that it could be specifically targeted for anti-parasitic or -microbial drug development.

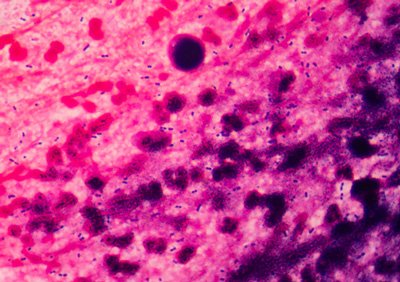

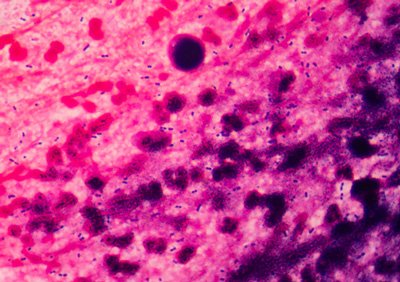

Using a combination of human or specially engineered mouse cells in vitro and in vivo animal models, study senior investigator Judy Lieberman, MD, PhD; study lead investigator Farokh Dotiwala, PhD, with a team lead by the Brazilian parasitologist Ricardo Gazzinelli, DSc, DVM, found that when an immune killer cell, such as a T-cell or natural killer (NK) cell, encounters a cell infected with any of three intracellular parasites (Trypanosoma cruzi, Toxoplasma gondii or Leishmania major), it releases three proteins that together kill both the parasite and the infected cell: perforin, which opens a hole in the membrane of the infected cell; granulysin, which enters the cell and attacks the surface of the parasite; and, granzymes, which enter the parasite and trigger a molecular cascade that kills the parasite.

The timing of this sequence appears to be tightly regulated so as to remove a parasitic infection without giving it a chance to spread. Lieberman’s team noted that in their model system, parasites began to die within 15 to 30 minutes, while the human or mouse cells they infected died some 45 minutes to an hour later. Their experiments also revealed that parasites died only when all three proteins were present.

Findings could open up new therapeutic approaches

The researchers were particularly struck by how much the granzyme-sparked cascade resembles apoptosis, a controlled form of cellular suicide that helps eliminate damaged or potentially cancerous cells. They found that granzymes interrupt metabolism within the parasite’s mitochondria. Levels of toxic molecules called reactive oxygen species subsequently skyrocket within the parasite. Shortly afterward, they noted, three things happen: the parasite’s DNA starts to condense, their nuclei start to fragment, and their membranes start to bulge or bleb.

These similarities to apoptosis have led the team to dub the process microbe-programmed cell death, or microptosis.

“The conventional wisdom is that programmed cell death only occurs in multicellular organisms,” Lieberman said. “But what our work suggests is that you can drive programmed cell death even in microbes. I think it’s probably a really ancient pathway.”

Parasitic infections such as trypanosomiasis and leishmanaisis remain a largely neglected but very important global health problem. Lieberman believes that the team’s findings could open up a new approach to therapy for these conditions.

Related topics

Antimicrobials, t-cells

Related organisations

Cancer Research