Study provides insight into muscle wasting in cancer patients

Posted: 4 February 2021 | Victoria Rees (Drug Target Review) | No comments yet

Using a mouse model, researchers found that cancer progression led to fewer skeletal muscle ribosomes, likely explaining muscle wasting.

A new study has provided clues into how muscle wasting happens on a cellular level in patients with cancer. The research was conducted at Penn State, US.

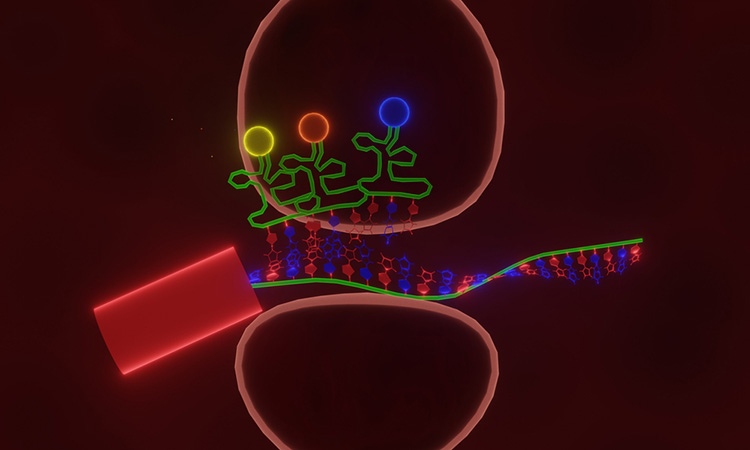

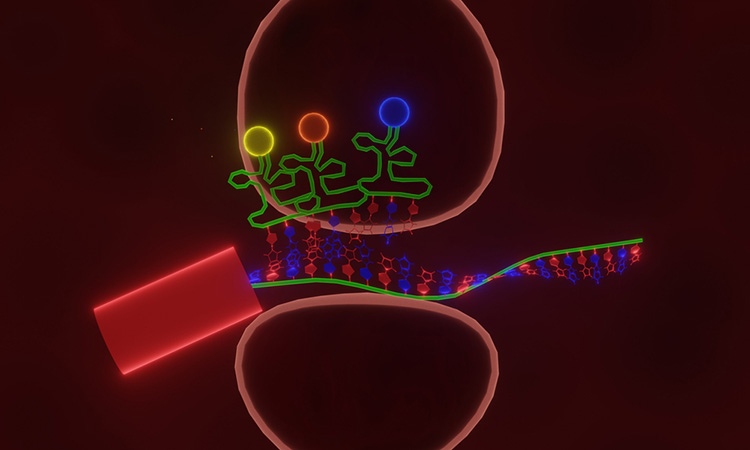

Using a mouse model of ovarian cancer, the researchers found that cancer progression led to fewer skeletal muscle ribosomes. As muscle mass is mainly determined by protein synthesis, having less ribosomes likely explains why muscles waste away in cancer.

“Not only is muscle wasting a common problem, but there is currently no cure or treatment, either. Now that we understand the mechanism better, we can move forward with trying to find ways to reverse that mechanism,” said lead researcher Associate Professor Gustavo Nader.

Drug Target Review has just announced the launch of its NEW and EXCLUSIVE report examining the evolution of AI and informatics in drug discovery and development.

In this 63 page in-depth report, experts and researchers explore the key benefits of AI and informatics processes, reveal where the challenges lie for the implementation of AI and how they see the use of these technologies streamlining workflows in the future.

Also featured are exclusive interviews with leading scientists from AstraZeneca, Auransa, PolarisQB and Chalmers University of Technology.

He continued that it is vital for scientists to understand precisely how and why muscle wasting – or cachexia – happens. “Most of the focus has been on protein degradation, where people have tried to block proteins from being chopped up or degraded in order to prevent the loss of muscle mass. However many of those efforts have failed and one reason may be because people forgot about the protein synthesis aspect of it, which is the process of creating new proteins. That is what we tackled in this study.”

For the study, the team used a pre-clinical mouse model of ovarian cancer with significant muscle loss. By using mice, the researchers were able to study the progression of cancer cachexia over time which would be difficult to do with human patients.

After analysing their results, the researchers found that mice with tumours experienced a rapid loss of muscle mass and a dramatic reduction in the ability to synthesise new proteins, which can be explained by a drop in the amount of ribosomes.

Then, the researchers investigated why the number of ribosomes was decreased. After examining the ribosomal genes, they found that once a tumour was present, the expression of the ribosomal genes started to decrease until it reached a level that made it impossible for the muscles to produce enough ribosomes to maintain enough protein synthesis to prevent muscle loss.

Nader said that while more research is needed, he hopes the findings can eventually contribute to prevent people from losing muscle mass and function.

“If we can better understand how muscles make ribosomes, we will be able to find new treatments to both stimulate growth and prevent muscle wasting,” Nader said. “This is especially important considering that current approaches to block tumour progression target the ribosomal production machinery and because these drugs are given systemically, they will likely affect all tissues in the body and will also impair muscle building.”

The findings were published in the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology Journal.

Related topics

Disease research, In Vivo, Protein, Research & Development, Targets

Related conditions

Cachexia, Cancer, Ovarian cancer

Related organisations

Penn State

Related people

Associate Professor Gustavo Nader