Non-hallucinogenic version of ibogaine could treat addiction and depression

Posted: 10 December 2020 | Victoria Rees (Drug Target Review) | 1 comment

A non-hallucinogenic version of the psychedelic drug ibogaine could treat psychiatric disorders, pre-clinical trials have shown.

A non-hallucinogenic version of the psychedelic drug ibogaine, with the potential for treating addiction, depression and other psychiatric disorders, has been developed by researchers at the University of California (UC), Davis, US.

“Psychedelics are some of the most powerful drugs we know of that affect the brain,” said Assistant Professor David Olson, senior author on the paper. “It’s unbelievable how little we know about them.”

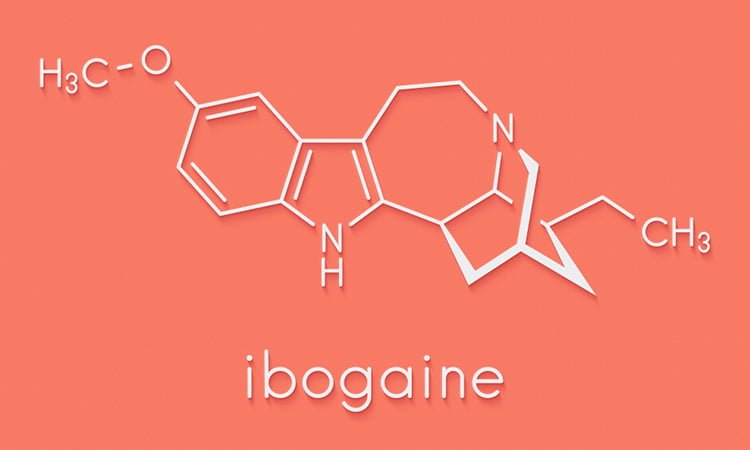

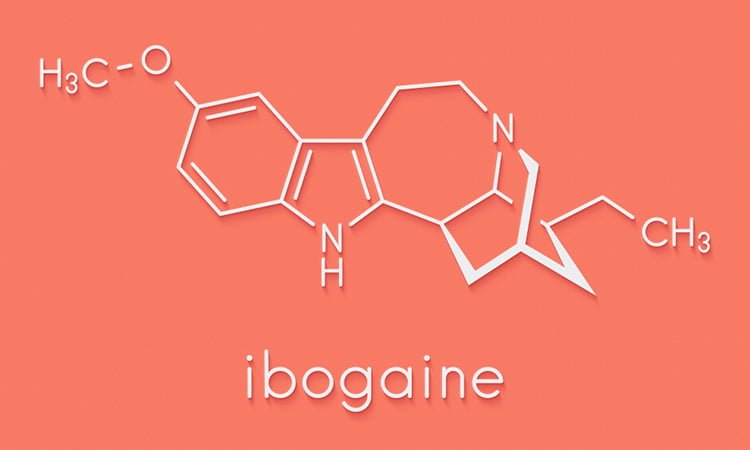

According to the researchers, ibogaine is extracted from the plant Tabernanthe iboga. There are anecdotal reports that it can have powerful anti-addiction effects such as reducing drug cravings and preventing relapse. However, there are also serious side effects, including hallucinations and cardiac toxicity and the drug is a Schedule 1 controlled substance under US law.

Olson’s laboratory at UC Davis is licensed to work with Schedule 1 substances. The team set out to create a synthetic analogue of ibogaine which retained therapeutic properties without the undesired effects of the psychedelic compound. They worked through a series of similar compounds by swapping out parts of the ibogaine molecule and engineered a new, synthetic molecule which they named tabernanthalog (TBG).

According to the researchers, unlike ibogaine, the new molecule is water-soluble and can be synthesised in a single step. Experiments with cell cultures and zebrafish showed that it is less toxic than ibogaine, which can cause heart attacks and has been responsible for several deaths.

The researchers found that TBG increased the formation of new dendrites (branches) in rat nerve cells and of new spines on those dendrites; this is similar to the effect of drugs like ketamine, LSD, MDMA and DMT (the active component in the plant extract ayahuasca) on connections between nerve cells.

TBG did not, however, cause a head twitch response in mice, which is known to correlate with hallucinations in humans. A series of experiments in rodent models of depression and addiction show that the new drug has promising positive effects.

Mice trained to drink alcohol cut back their consumption after a single dose of TBG. Rats were trained to associate a light and tone with pressing a lever to get a dose of heroin. When the opiate is taken away, the rats develop signs of withdrawal and press the lever again when given the light and sound cues. Treating the rats with TBG had a long-lasting effect on opiate relapse.

Olson thinks that TBG works by changing the structure of neurons in key brain circuits involved in depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and addiction.

“We’ve been focused on treating one psychiatric disease at a time, but we know that these illnesses overlap,” Olson said. “It might be possible to treat multiple diseases with the same drug.”

The results of the study were published in Nature.

Related topics

Drug Development, Drug Leads, Drug Targets, In Vivo, Target molecule, Targets, Therapeutics

Related conditions

Addiction, Depression, Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), psychiatric disorders

Related organisations

University of California Davis

Related people

Assistant Professor David Olson

Are there clinical trials or human studies available?