Optogenetics used to control diabetes without medication

Posted: 6 November 2019 | Drug Target Review | No comments yet

Scientists in the US have successfully controlled glucose levels in diabetic mouse models without the need for medication.

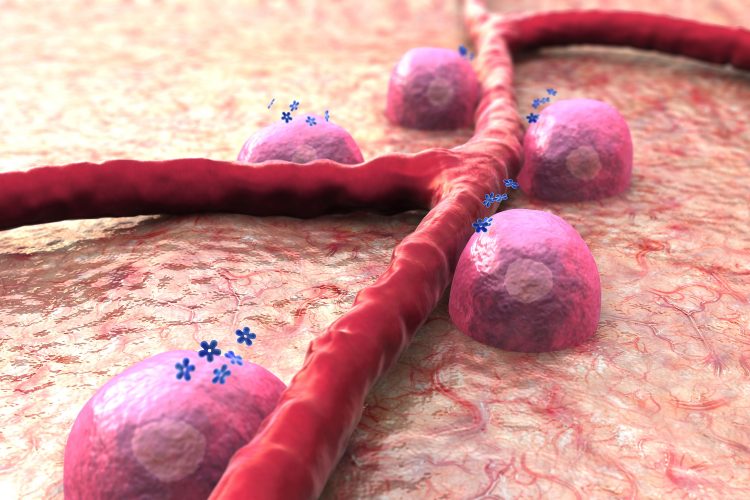

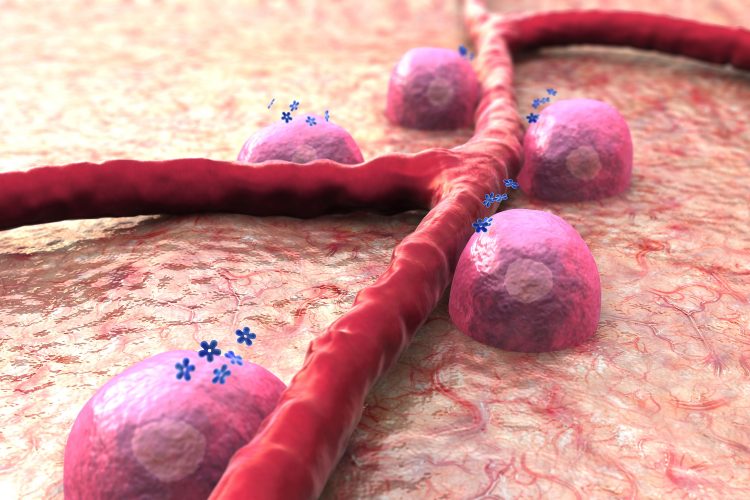

Tufts University researchers have transplanted engineered pancreatic beta cells into diabetic mice, and caused the cells to produce more than double the usual amount of insulin by exposing them to light. These light-switchable cells, the use of which is termed ‘optogenetics’, are designed to compensate for lower insulin production in diabetic individuals. The study demonstrated that glucose levels can be controlled in a mouse model of diabetes without pharmacological intervention.

Insulin is a hormone that plays a central role in precisely controlling levels of circulating glucose. In type 2 diabetes – the most common form of the disease – the cells of the body become inefficient at responding to insulin and as a consequence, glucose in circulation can become dangerously high (hyperglycemia) while the pancreas cannot produce enough insulin to compensate. In type 1 diabetes, the beta cells that produce insulin are destroyed by the immune system, resulting in a complete absence of the hormone.

Current treatments include the administration of drugs that enhance the production of insulin by pancreatic beta cells, or direct injection of insulin to supplement the naturally produced supply. In both cases, regulation of blood glucose becomes a manual process that can lead to spikes and valleys and have harmful long-term effects.

The researchers sought to develop a new way to amplify insulin production while maintaining the important real-time link between the release of insulin and concentration of glucose in the bloodstream. This was achieved by utilising optogenetics, which relies on proteins that change their activity on demand with light.

Researchers found that transplanting the engineered pancreatic beta cells under the skin of diabetic mice led to improved tolerance and regulation of glucose, reduced hyperglycaemia, and higher levels of plasma insulin when subjected to illumination with blue light.

“It’s a backwards analogy, but we are actually using light to turn on and off a biological switch,” said Emmanuel Tzanakakis, professor of chemical and biological engineering at the School of Engineering at Tufts University and corresponding author of the study. “In this way, we can help in a diabetic context to better control and maintain appropriate levels of glucose without pharmacological intervention. The cells do the work of insulin production naturally and the regulatory circuits within them work the same; we just boost the amount of cAMP transiently in beta cells to get them to make more insulin only when it’s needed.”

The blue light acts as a switch turning the cells to boost mode. Such optogenetic approaches utilising light-activatable proteins to modulate cell function are being explored in many biological systems, fuelling the development of a new genre of treatments.

The study was published in ACS Synthetic Biology.

Related topics

Hormones, Optogenetics, Research & Development

Related conditions

Diabetes

Related organisations

Tufts University

Related people

Emmanuel Tzanakakis