Blood-brain barrier role in Alzheimer’s patients revealed by tissue model

Posted: 13 August 2019 | Rachael Harper (Drug Target Review) | No comments yet

A new study has found that damage caused by Alzheimer’s allows toxins to enter the brain, further harming neurons.

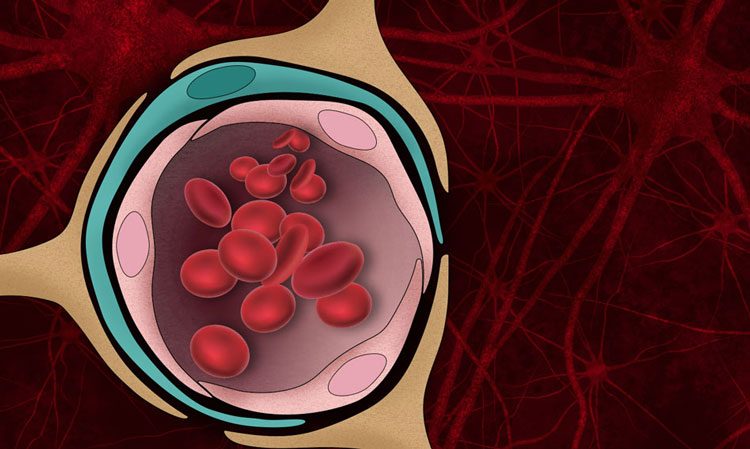

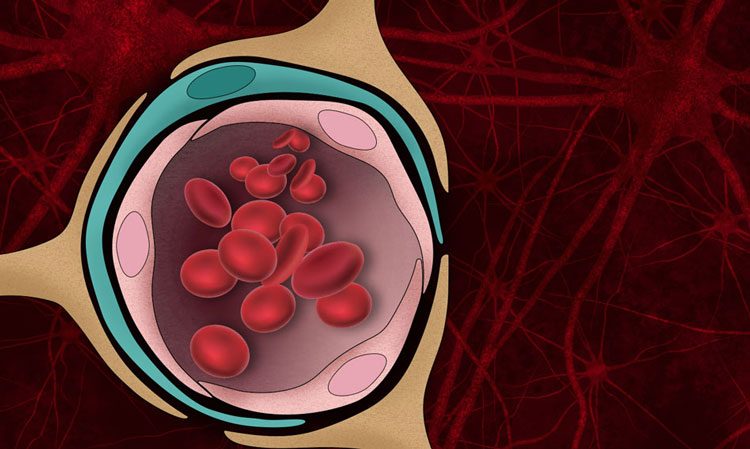

The blood-brain barrier — the normally tight border that prevents harmful molecules in the bloodstream from entering the brain — can be damaged by the protein aggregates that form in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients (credit: Christine Daniloff, MIT).

MIT engineers have developed a tissue model that mimics beta-amyloid’s effects on the blood-brain barrier, and used it to show that this damage can lead molecules such as thrombin to enter the brain and cause additional damage to Alzheimer’s neurons.

“We were able to show clearly in this model that the amyloid-beta secreted by Alzheimer’s disease cells can actually impair barrier function, and once that is impaired, factors are secreted into the brain tissue that can have adverse effects on neuron health,” said Roger Kamm, the Cecil and Ida Green Distinguished Professor of Mechanical and Biological Engineering at MIT.

The researchers used the tissue model to show that a drug that restores the blood-brain barrier can slow down the cell death seen in Alzheimer’s neurons.

The study was centred around cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) and its role in Alzheimer’s, by modeling brain and blood vessel tissue on a microfluidic chip.

“What we were trying to do from the start was generate a model that we could use to understand the interactions between Alzheimer’s disease neurons and the brain vasculature,” Kamm continued.

The researchers devised a way to grow these cells in a microfluidic channel, where they produce and secrete beta-amyloid protein. On the same chip, in a parallel channel, the researchers grew brain endothelial cells, which are the cells that form the blood-brain barrier. An empty channel separated the two channels while each tissue type developed.

After 10 days of cell growth, the researchers added collagen to the central channel separating the two tissue types, which allowed molecules to diffuse from one channel to the other. They found that within three to six days, beta-amyloid proteins secreted by the neurons began to accumulate in the endothelial tissue, which led the cells to become leakier. These cells also showed a decline in proteins that form tight junctions, and an increase in enzymes that break down the extracellular matrix that normally surrounds and supports blood vessels.

As a result of this breakdown in the blood-brain barrier, thrombin was able to pass from blood flowing through the leaky vessels into the Alzheimer’s neurons.

The researchers then decided to test drugs that have previously been shown to solidify the blood-brain barrier in simpler models of endothelial tissue, finding that the tissue treated with one of these drugs, etodolac, the blood-brain barrier became tighter, and neurons’ survival rates improved.

The team are now working with a drug discovery consortium to look for other drugs that might be able to restore the blood-brain barrier in Alzheimer’s patients.

The study was published in the journal, Advanced Science.

Related topics

Analysis, Disease research, Drug Discovery, Neurons, Protein

Related conditions

Alzheimer's

Related organisations

MIT

Related people

Roger Kamm