Therapeutic strategy to prevent gastrointestinal disease

Posted: 2 April 2019 | Drug Target Review | No comments yet

New approach restores epithelial function in diarrhoea and inflammatory bowel disease models…

A team led by investigators from Brigham and Women’s Hospital have developed an approach that could help prevent gastrointestinal disease.

In a study published in Nature Medicine, the researchers report new evidence suggesting that specifically targeting one version of the enzyme myosin light chain kinase (MLCK1) may be effective in both preventing and treating gastrointestinal disease by preserving and restoring barrier function, respectively.

“This represents a completely novel, non-toxic approach to intestinal barrier restoration and treatment of inflammatory bowel disease,” said corresponding author Jerrold Turner, MD, PhD, of the Department of Pathology at the Brigham.

“Our study indicates that MLCK1 is a viable target for preserving epithelial barrier function in intestinal diseases and beyond. This therapeutic approach may help break the cycle of inflammation that drives so many chronic diseases.”

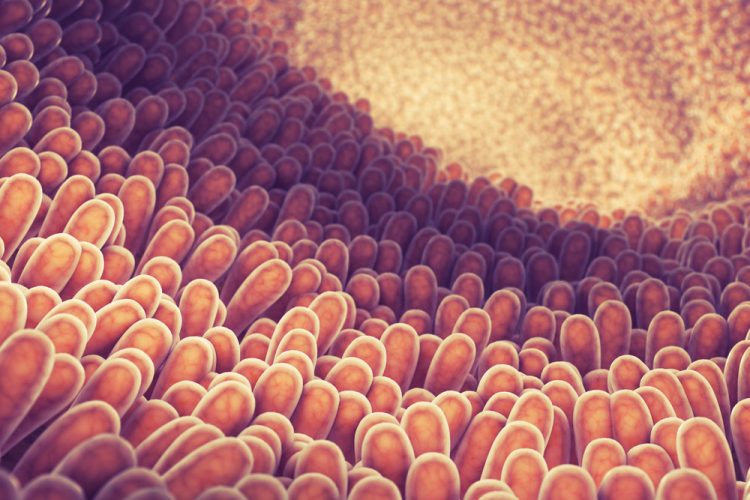

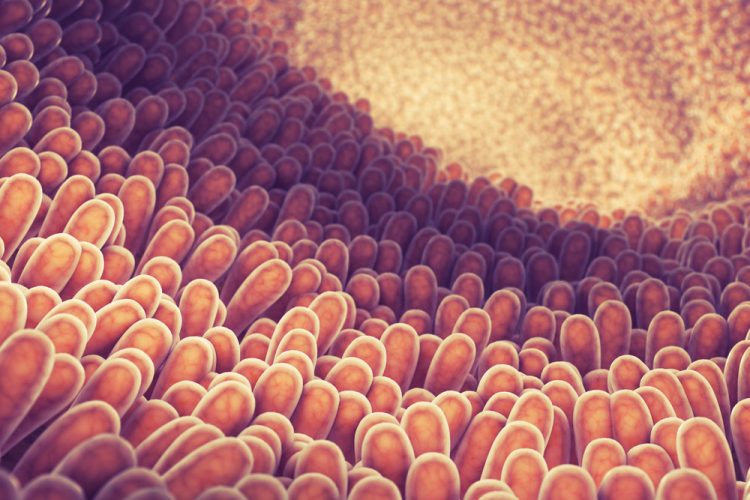

Food allergies, coeliac disease, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), diarrhoea and other gastrointestinal diseases have something in common: all have been linked to epithelial barrier loss. The gut epithelial barrier – that critical lining of cells in the gut that must allow nutrients into the body while keeping food-borne microbes out – can be compromised during intestinal inflammation and cause disease.

While many of the molecular mechanisms that trigger gastrointestinal diseases remain a mystery, previous research has found that one enzyme, known as myosin light chain kinase (MLCK), plays a critical role. MLCK, however, is also essential for critical functions in gut epithelia and other cell types. This makes direct inhibition of MLCK impossible, as it would result in many toxic and systemic side effects.

Other forms of MLCK can be found throughout the gut lining, in various epithelia and in smooth muscle. But the MLCK1 isoform is particularly expressed in the villous enterocytes – intestinal cells that sit in the finger-like projections that extend into the lumens of the small intestine – and corresponding surface cells of the colon.

To lay the groundwork for targeting only MLCK1, Turner and his team solved the crystal structure of the region that distinguishes MLCK1 from other variants. They then used computer modelling to screen approximately 140,000 molecules, looking for one that could dock into this region like a key in a lock.

The team found a molecule, which they named Divertin, that fits neatly into this pocket. Divertin prevented inflammation-induced barrier loss without compromising key MLCK enzymatic functions in epithelia and smooth muscle.

In mouse models of inflammatory bowel disease and diarrhoea, Divertin corrected barrier dysfunction and reduced disease severity. When given prophylactically, Divertin prevented disease development and progression. This suggests that Divertin might be a new, non-immunosuppressive means to maintain remission, and prevent disease flares, in patients with IBD.

Turner and colleagues note that targeting MLCK1 to prevent barrier loss and restore function could also be useful in other diseases where the epithelial barrier is compromised, including coeliac disease, atopic dermatitis, pulmonary infection and acute respiratory distress syndrome, multiple sclerosis, and graft versus host disease (GVHD).

In a study published recently in The Journal of Clinical Investigation, the same research team presented evidence that MLCK drives the continuation of GVHD, a complication that can arise after a transplant when donor immune cells begin attacking the organs of a transplant recipient. While Divertin was not tested in GVHD, the data suggest that it may be an effective therapy.

Related topics

Enzymes, Molecular Biology, Screening

Related conditions

Coeliac disease, food allergy, Gastrointestinal disease, Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

Related organisations

Brigham and Women's Hospital

Related people

Jerrold Turner