Np63a should be targeted in squamous cell carcinomas

Posted: 19 September 2018 | Iqra Farooq (Drug Target Review) | No comments yet

A team of researchers have identified that to target p63, both TGFB2 and RHOA tumour suppressor genes should be activated…

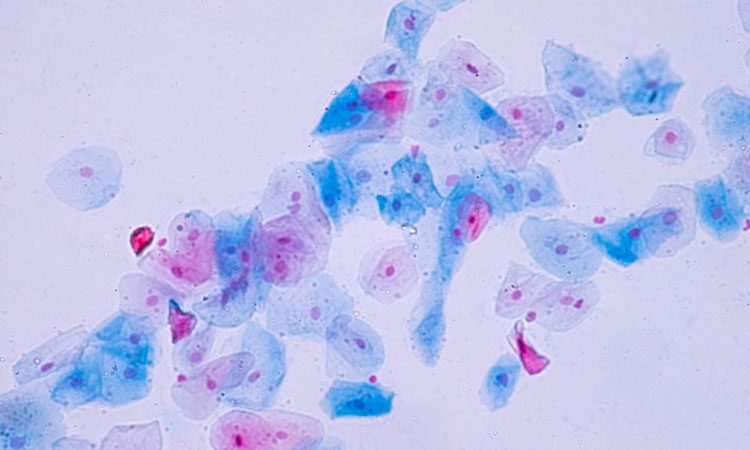

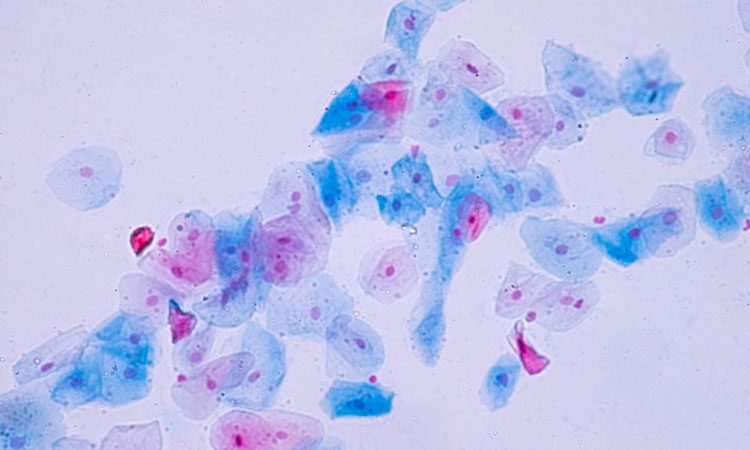

A team of researchers studied p63 activity in squamous cell carcinoma of the lung. They identified an actionable path towards drug discovery against this cause of cancer.

Flaws in p63 during embryonic development can result in certain birth defects, such as cleft palette, missing limbs or fused fingers. Generally, after this p63 stays in the genome, silently watching.

If accidentally reactivated in the adult genome, it could result in cancer. Over half of all squamous cell carcinomas, such as those in the lungs, breast, skin and head/neck, involve excess activity from p63.

For a long time, scientists have known that p63 causes squamous cell cancers. Although it has been approached, p63 cannot be simply ‘turned off’. The research team decided to investigate the action of p63 and possible methods to interfere with its action in order to shield patients from its cancerous effects.

“The question that initiates this study is what is this oncogene, p63, doing to drive cell proliferation and why too much of it would cause cancer,” said Dr Joaquin Espinosa.

Dr Espinosa and his colleagues ran the cells through a genome-wide CRISPR screen – a cutting-edge technology enabling the analysis of thousands of genes in a single experiment. The Cancer Centre Functional Genomics Shared Resource at the University of Colorado was used for this purpose.

The team began by analysing squamous cell lung carcinoma cells that required a product of p63, Np63a, in order to proliferate. They turned off the production of Np63a and explained how Np63a had been suppressing the action of tumour-suppressor genes. Without Np63a, these tumour-suppressor genes were active again and continued to prevent cells proliferating.

“It’s an example of the classic tug-of-war between oncogenes and tumor-suppressor genes – based on this balance, you either have cancer or you don’t,” said Dr Espinosa.

The team used CRISPR to identify which tumour suppressor genes Np63a was preventing from working, and found the key genes to be TGFB2 and RHOA.

“We screened the entire genome and there was one molecular pathway, super clean and super clear, that Np63a needed to turn off to drive the growth of squamous cell carcinoma cells,” explained Dr Espinosa.

The group identified, from the Cancer Genome Atlas, that from published data of 518 lung squamous cell carcinoma, cancers with Np63a, around 80 percent showed inactivated TGFB2 RHOA.

The researchers conclude how the path towards the therapy against Np63a is simply to activate TGFB2 and RHOA.

“This is a potentially druggable pathway that is driving the progression of squamous cell carcinomas,” Dr Espinosa said. “The challenge now is to exploit this knowledge for therapeutics, to find a way to reactivate the TGFB/RHOA pathway to save the lives of patients with cancers.”

The study was published in the journal Cell Reports.

Related topics

Analysis, Analytical techniques, CRISPR, Disease research, Drug Targets, Oncology, Research & Development, Therapeutics

Related conditions

Cancer, squamous cell carcinoma

Related organisations

University of Colorado Cancer Centre

Related people

Dr Joaquin Espinosa