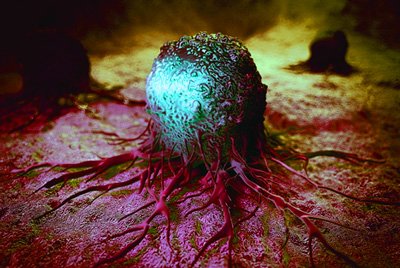

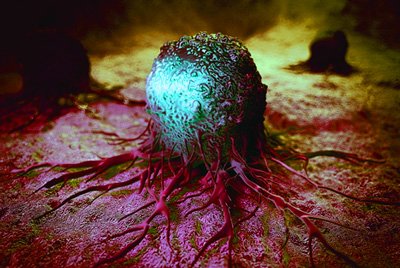

Cancers can resist treatment by ‘stealing’ blood vessels

Posted: 8 April 2016 | Victoria White, Digital Content Producer | No comments yet

A new study is the first to show that tumours can become resistant to drugs over time by learning to steal normal blood vessels from surrounding tissue…

A new study is the first to show that tumours can become resistant to drugs over time by learning to steal normal blood vessels from surrounding tissue – a process that researchers call vessel co-option.

The process of new blood vessel growth – angiogenesis – is important for cancers to grow, and several anti-angiogenic drugs have been developed to combat it. However, cancers often become resistant to these drugs, through mechanisms which until now were poorly understood.

The study, from researchers at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, and Sunnybrook Research Institute, University of Toronto, shows it could be possible to treat cancers by designing new therapies that block both vessel co-option and angiogenesis. These may be more effective than existing treatments, which only block angiogenesis.

In the study, scientists used mice to examine how a type of liver cancer called hepatocellular carcinoma can become resistant to an anti-angiogenic drug called sorafenib. They discovered that tumours which responded to treatment initially relied mainly on growing their own blood vessels, but developed resistance to treatment by actively stealing the normal pre-existing blood vessels of the liver instead.

Study may have implications for other cancers

The researchers believe their study may have implications not only for the treatment of liver cancer, but also for other cancer types including metastatic breast cancer and metastatic bowel cancer. Scientists at The Institute of Cancer Research are currently investigating the implications of this research for these other cancer types.

Interestingly, the researchers also found that the switch to vessel co-option was reversible. On stopping treatment, the tumours switched back to using angiogenesis – providing a potential explanation as to why some patients can respond again to the same anti-angiogenic drug after they have a ‘treatment holiday.’

Because there are no existing drugs that target vessel co-option, the researchers also carried out experiments to identify how vessel co-option works. They discovered that the cancer cells increase their ability to move when they co-opt vessels, suggesting that targeting cancer cell movement might be used to block vessel co-option.

Commenting on the research, study co-leader Dr Andrew Reynolds, Leader of the Tumour Biology team at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, said: “Our study is the first to show that cancers can adapt to treatment by actively co-opting blood vessels from nearby tissues as a mechanism of drug resistance.

“In the future, we hope our results will lead to the development of new drug types that target vessel co-option. We believe that drugs which are designed to target vessel co-option could be particularly effective when used alongside existing therapies that block new blood vessel growth.”

Dr Reynolds describes the research in this video:

Related topics

Oncology

Related organisations

The Institute of Cancer Research (ICR)