DNA origami successfully used to kill leukaemia cells

Posted: 24 February 2016 | Victoria White | No comments yet

Researchers at The Ohio State University are working on a new way to treat drug-resistant cancer that uses DNA origami packaging…

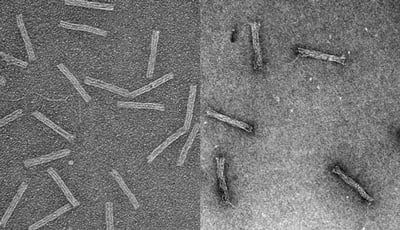

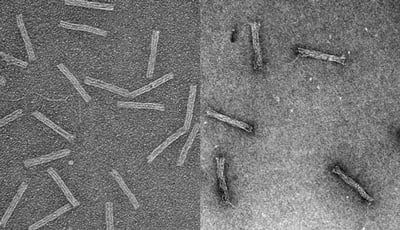

These electron microscope images show the structures empty (left) and loaded with the cancer drug daunorubicin (right). Image by Randy Patton, courtesy of The Ohio State University.

Researchers at The Ohio State University are working on a new way to treat drug-resistant cancer that uses DNA to hide a common cancer drug.

In laboratory tests, leukaemia cells that had become resistant to the drug absorbed it and died when the drug was hidden in a capsule made of folded up DNA.

Previously, other research groups have used the same packaging technique, known as “DNA origami,” to foil drug resistance in solid tumours. This is the first time researchers have shown that the same technique works on drug-resistant leukaemia cells.

The study involved a preclinical model of acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) that has developed resistance against the drug daunorubicin. Specifically, when molecules of daunorubicin enter an AML cell, the cell recognises them and pumps them back out through openings in the cell wall. It’s a mechanism of resistance that John Byrd of The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Centre compared to sump pumps that draw water from a basement.

He and Carlos Castro, assistant professor of mechanical engineering, lead a collaboration focused on hiding daunorubicin inside a kind of molecular Trojan horse that can bypass the pumps so they can’t eject the drug from the cell.

“Cancer cells have novel ways of resisting drugs, like these pumps, and the exciting part of packaging the drug this way is that we can circumvent those defences so that the drug accumulates in the cancer cell and causes it to die,” said Byrd, a professor of internal medicine and director of the Division of Haematology. “Potentially, we can also tailor these structures to make them deliver drugs selectively to cancer cells and not to other parts of the body where they can cause side effects.”

“DNA origami nanostructures have a lot of potential for drug delivery, not just for making effective drug delivery vehicles, but enabling new ways to study drug delivery. For instance, we can vary the shape or mechanical stiffness of a structure very precisely and see how that affects entry into cells,” added Castro, director of the Laboratory for Nanoengineering and Biodesign.

In tests, the researchers found that AML cells, which had previously shown resistance to daunorubicin, effectively absorbed drug molecules when they were hidden inside tiny rod-shaped capsules made of DNA. Under the microscope, the researchers tracked the capsules inside the cells with fluorescent tags.

Each capsule measures about 15 nanometers wide and 100 nanometers long – about 100 times smaller than the cancer cells it’s designed to infiltrate. With four hollow, open-ended interior compartments, the researchers say it looks like an elongated cinder block.

Postdoctoral researcher Christopher Lucas said that the design maximises the surface area available to carry the drug. “The way daunorubicin works is it tucks into the cancer cell’s DNA and prevents it from replicating. So we designed a capsule structure that would have lots of accessible DNA base-pairs for it to tuck into. When the capsule breaks down, the drug molecules are freed to flood the cell.”

Leukaemia cells died within 15 hours of consuming the DNA origami capsules

Castro’s team designed the capsules to be strong and stable, so that they wouldn’t fully disintegrate and release the bulk of the drugs until it was too late for the cell to spit them back out. And that’s what they saw with a fluorescence microscope – the cells drew the capsules into the organelles that would normally digest them, if they were food. When the capsules broke down, the drugs flooded the cells and caused them to disintegrate. Most cells died within the first 15 hours after consuming the capsules.

This work is the first effort for the engineers in Castro’s lab to develop a medical application for the DNA origami structures they have been building. Castro said he hopes to create a streamlined and economically viable process for building the capsules – and other shapes as well – as part of a modular drug delivery system.

Byrd said the technique should potentially work on most any form of drug-resistant cancer if further work shows it can be effectively translated to animal models, though he stopped short of suggesting that it would work against pathogens such as bacteria, where the mechanisms for drug resistance may be different.

Related topics

Drug Delivery

Related conditions

Leukaemia