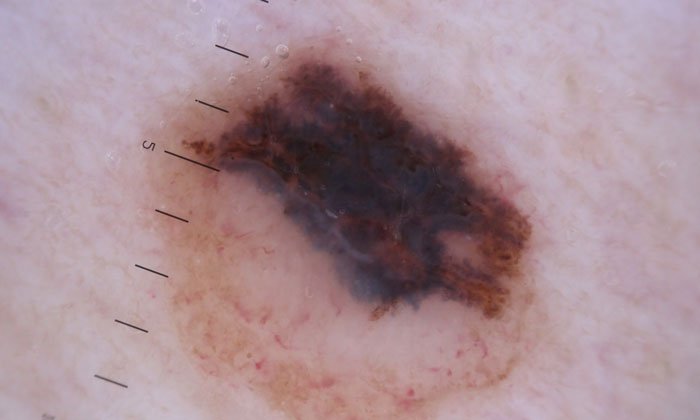

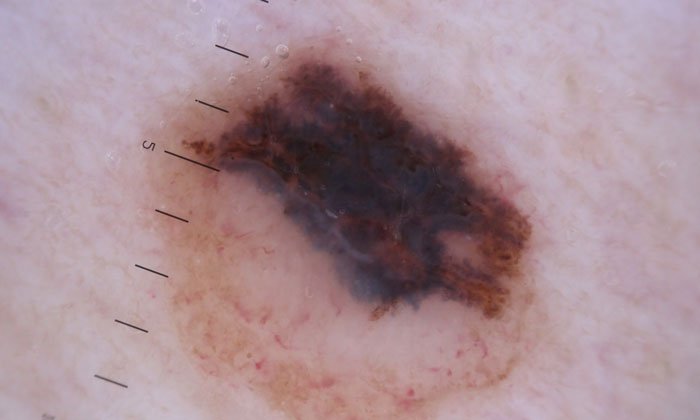

Disrupting macrophage action aids melanoma immunotherapy success

Posted: 13 April 2018 | Drug Target Review | No comments yet

Scientists in Switzerland have uncovered a potential means of increasing effective treatment of melanomas with immunotherapy, by disrupting the action of macrophages.

Immunotherapies are treatments that stimulate a patient’s immune cells to attack tumours. They can be very effective in melanoma – a common and aggressive form of skin cancer – but still fail in the majority of patients. To address this, researchers are trying to identify the factors that enable successful immunotherapy, as well as those that may limit it – and macrophages have been identified as possible barrier to overcome. The ultimate goal is to open new avenues for immunotherapies that are more broadly effective in melanoma, and potentially other cancer types.

Certain immune cells, called CD8 T cells (or cytotoxic T lymphocytes), can recognise and kill melanoma cells, thus having the potential to eradicate tumours. Immunotherapies stimulate the CD8 T cells to attack the tumour more vigorously, but the activity of CD8 T cells can be suppressed by other immune cells present in the tumour.

Macrophages lead the resistance

Studying a subset of melanoma patients, researchers led by Michele De Palma at EPFL (École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne) and Daniel Speiser at the University of Lausanne have identified macrophages as the culprits that drive resistance to a leading immunotherapy, and the mechanism is known as PD-1 checkpoint blockade.

Commenting on the fine balance between the necessity of macrophages and their overexpression, De Palma said: “The existence of immune cells that either execute or suppress cytotoxic immune responses is essential for limiting the potentially deleterious effects of an uncontrolled immune response, a condition that may lead to auto-immunity or organ damage.”

“The problem is that tumours hijack these regulatory mechanisms to their own benefit, so that they can grow largely unchecked by the immune system”.

By analysing samples obtained from the patients’ tumours, Speiser and his colleagues found that the CD8 T cells release signals that indirectly attract the macrophages to the tumours, establishing what they refer to as a “dangerous liaison” in melanoma.

“It is a sort of vicious cycle,” says Speiser. “The good side of the coin is that the CD8 T cells get activated by certain tumour antigens and initiate a potentially beneficial immune response against the tumour. The bad side is that, when activated, the CD8 T cells also induce the production of a protein in melanoma, called CSF1, which attracts the macrophages.” Indeed, melanomas that attract many CD8 T cells frequently end up containing many macrophages, which can weaken the efficacy of PD-1 immunotherapy.

Once recruited en masse to the tumour, macrophages suppress the CD8 T cells and dampen the anti-tumoural immune response. However, when the scientists used a drug to specifically eliminate the macrophages in experimental models of melanoma, they found that the efficacy of PD-1 checkpoint blockade immunotherapy was greatly improved.

Immunotherapy coupled with macrophage disruption

The findings support the clinical testing of agents that disrupt macrophages in combination with PD-1 immunotherapy in patients whose melanomas contain high numbers of both CD8 T cells and macrophages.

“As opposed to targeted therapies that hit specific oncogenes responsible for the growth of the tumour, immunotherapies largely lack biomarkers that can predict whether a patient will respond or not to the treatment”, says De Palma. “Our study suggests that assessing the abundance of macrophages and the contextual presence of CD8 T-cells – for example by measuring genes that are specifically expressed by these cells – may serve to stratify patients who are amenable to more effective immunotherapy combinations,” concludes Speiser.

Related topics

Disease research, Immunotherapy

Related conditions

Melanoma

Related organisations

Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale De Lausanne, University of Lausanne

Related people

Daniel Speiser - University of Lausanne, Michele De Palma - EPFL