Inhibiting METTL3 destroys AML cells without harming normal blood cells

Posted: 28 November 2017 | Dr Zara Kassam (Drug Target Review) | No comments yet

An unexpected drug target for acute myeloid leukaemia could open new avenues to develop effective treatments against the potentially lethal disease…

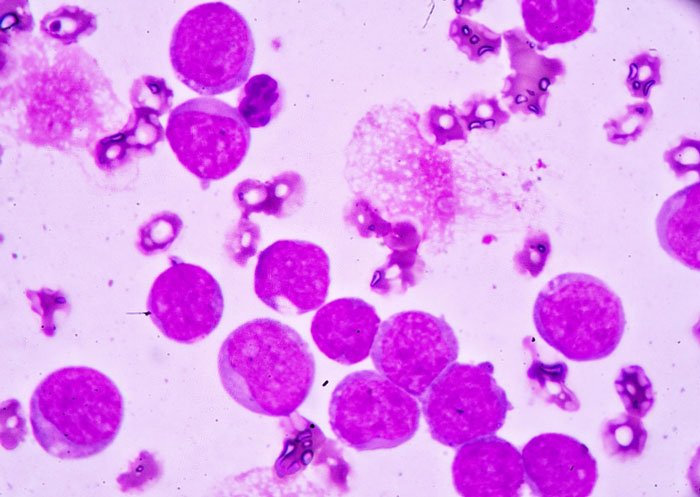

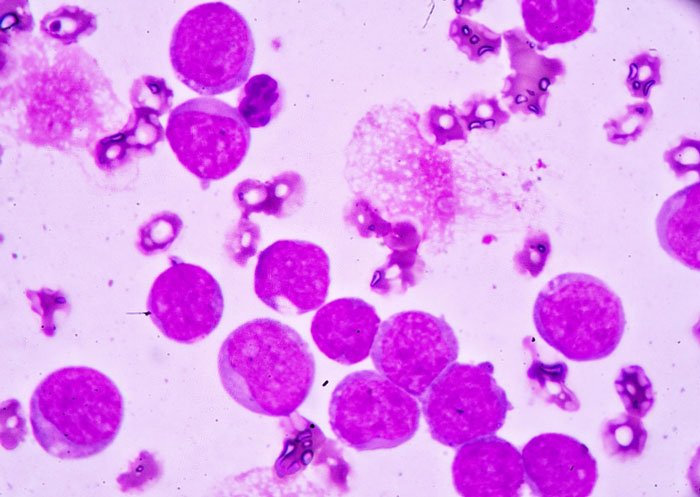

A study has found an unexpected new drug target for acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) that could open new avenues to develop effective treatments against this potentially lethal disease. Researchers from the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, the Gurdon Institute and their collaborators show that inhibiting the METTL3 gene destroys human and mouse AML cells without harming non-leukaemic blood cells.

The study goes on to reveal why METTL3 is required for AML cell survival, by deciphering the new mechanism it uses to regulate several other leukaemia genes.

To identify potential new ways to treat AML, the researchers used CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing technology to screen cancer cells for vulnerable points. They created mouse leukaemia cells with mutations in the genes that may be targeted in human AML cells and systematically tested each gene, finding which were essential for AML survival.

The researchers ended up with 46 likely candidate genes, many of which produce proteins that could modify RNA. Amongst these, METTL3 was one of the genes with the strongest effect. They found that whilst it was essential for the survival of AML cells, it was not required for healthy blood cells, making it a good potential drug target.

Professor Tony Kouzarides, the joint project leader from the Gurdon Institute, University of Cambridge, said: “New treatments for AML are desperately needed and we have been looking for genes that would be good drug targets. We identified the methyltransferase enzyme METTL3 as a highly viable target against AML. Our study will inspire pharmaceutical efforts to find drugs that specifically inhibit METTL3 to treat AML.”

For proteins to be produced in a cell, the DNA is transcribed into messenger RNA, which is then translated into the proteins that the cell needs. However, modifications to the RNA can control if a protein is produced. This is a recently-discovered type of gene regulation called RNA editing.

This study uncovered an entirely new mechanism of gene regulation in AML that operates through modifications of RNA

Having found a potential target in METTL3, the researchers investigated how it worked. They discovered that the protein produced by METTL3 bound to the beginning of 126 different genes, including several required for AML cell survival. Then, as RNAs were produced, the METTL3 protein added methyl groups to their middle section, something which had not been previously observed.

The researchers found that these middle methyl groups increased the ability of the RNAs to be translated into proteins. They then showed that when METTL3 was inhibited, no methyl groups were added to the RNA. This prevented the production of their essential proteins so the AML cells started dying.

“This study uncovered an entirely new mechanism of gene regulation in AML that operates through modifications of RNA. We discovered that inhibiting the methyltransferase activity of METTL3 would stop the translation of a whole set of proteins that the leukaemia needs. This mechanism shows that a drug to inhibit methylation could be effective against AML without affecting normal cells,” said Dr Tzelepis.

Dr George Vassiliou, joint project leader from the Sanger Institute and Consultant Haematologist at Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Trust, said: AML is a feared disease that affects people all around the world, our treatments have changed little for decades and outcomes remain poor for the majority of patients. We believed that we had to think differently and look in new places for ways to treat the disease and in METTL3 we have found an exciting new target for drugs. We hope that this discovery will lead to more effective treatments that will improve the survival and the quality of life of patients with AML.”

The study has been reported in the journal Nature.

Related topics

CRISPR, Drug Targets, Oncology, RNAs

Related conditions

acute myeloid leukaemia

Related organisations

Gurdon Institute, University of Cambridge, Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute

Related people

Dr George Vassiliou, Professor Tony Kouzarides